Albert E. Daniel – His Life Works

(Summarized by Jessica Hornbeck.)

Magda Smith, long-time St. John resident, student of art history and former Director of the Virgin Islands Humanities Council, introduced those gathered at our November membership meeting to native Virgin Islands artist Albert E. Daniel with his own words:

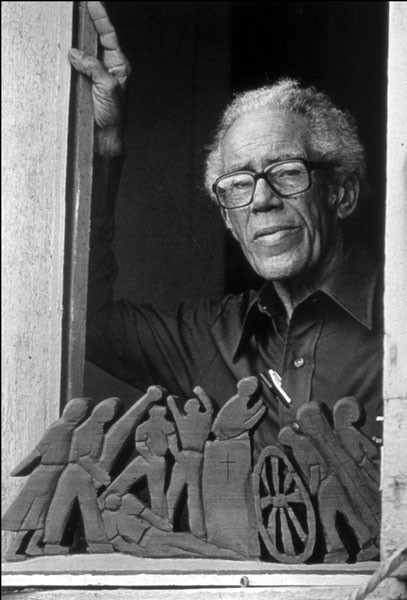

Albert E. Daniel (with Mass Hysteria), 1980

(Photo by Ray Miles)

“Never had a lesson in my life, some call me a hit and a miss, but I seldom miss. You can go to a thousand schools, they can teach you the technique of art, but expression, you must have it inside, they can’t put expression into you.”

Smith and Daniel met in the late 1970s. On numerous occasions over the next few years, Smith and Daniel discussed the artist’s work and during these times he shared his vision and ambitions. Daniel passed in 1982, and Smith mounted the first of several retrospectives of his work in 1987. According to Smith, Daniel was a self-taught artist, who developed over the course of his career, “the ability to project his inner vision on canvas.” It was this ability that made him the “original” that he once told his younger brother he wanted to become.

(Albert Daniel, never lived anywhere but St. Thomas and saw very little of the world. However, through the keen observation of the changes that took place in his island home, with his inner eye he saw into the soul of every man, and expressed through his art a vision that has meaning for us all.)

Magda’s talk, amply supported with images of his paintings and wood sculptures, traced Daniel’s life from his birth on May 16th, 1897, Daniel began his career by “getting the feel of the paint.” He did this by copying anything he could find to improve his skills, including imitating various European styles of painting. Daniel, a devout Catholic, once told Smith that he “prayed for inspiration” in his search for a unique style to express his message. In the mid-1940s, with the financial support of his wife Agnes Brouwer, Daniel decided to dedicate himself full-time to his art.

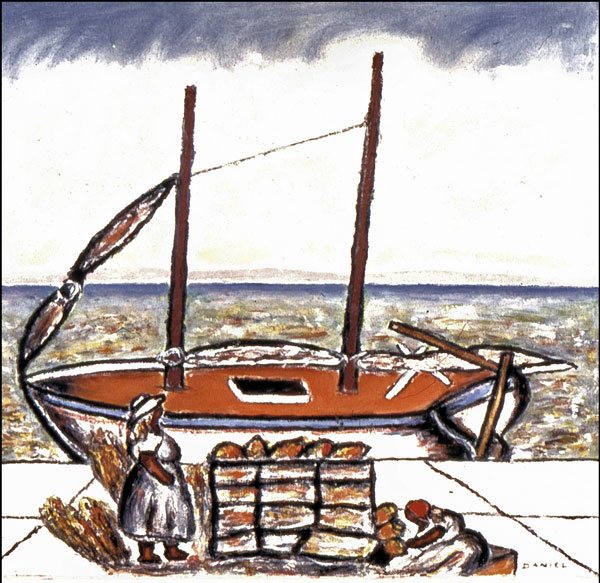

Ah Wondar Tis Fur How Lang *** (1970s acrylic)

(In this waterfront scene, Daniel has one of the market women say to the other in the vernacular: “Ah Wondar Tis Fur How Lang Dismango Kepmae Standingyhar Waitingpunhim Ahgat Togo Homtocuk Furmaiechirrundem.” (I wonder how long this man is going to keep me standing here, waiting for him. I have to go home to cook for my children). In symbolic terms the painting makes a statement on the island life of the past: The balanced composition, underscored by the perspective lines, reflects the stability and order of the traditional way of life. The sloop represents the speed of yesterday–when time went softly by–while the market women with their wares symbolize the daily struggle for existence which finds release in the after-life, beckoning in glowing colors on the horizon. Daniel would see in every sunset the gleaming walls of paradise. [Private collection])

Daniel’s first significant recognition as an artist came with the acceptance of his painting of a market vendor for exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair. This painting confirmed him in his chosen subject matter—the market vendor, fisherman, dock worker and farm laborer who formed the backbone of Virgin Islands society. By the late 1950s, Daniel had found his own unique style. Disregarding the laws of perspective, he depicts figures in frontal or profile representations; he captures the typical mannerism of his subjects with expressive vitality. In Smith’s words, “color and movement are the heart and soul of Daniel’s painting and sculpture.”

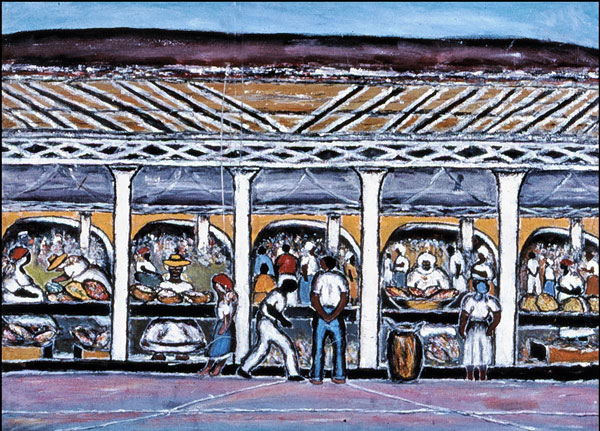

Market Square (1960s acrylic)

With the demise of the traditional way of life in the 1960s, Daniel turned his creative efforts to a restoration of the past. Stylistically mature, Daniel manipulates pictorial elements for symbolic and decorative purposes. In his “memory paintings,” the artist conjures up the past using artifacts—the Danish colonial flag, the sack of coal, the beast of burden, and the market tray, emblematic of the traditional life style. During this period, Daniel’s market woman and laborer become critical observers of the social changes brought about by commercialization, with his themes often summarized with titles and verses drawn from 19th century poetry and sayings in Virgin Islands dialect on the back of his works. The best known of his symbols is the pole, or “staff of life,” which represents the presence of the Almighty in the lives of his subjects.

(In this Market Square scene we see the integration of stylistic elements in a harmonious whole, symbolic of a dynamic, well-ordered society. The vertical orientation of the perspective lines that defines the roof of the bungalow and the foreground is carried onward in the bungalow columns and the arches of Mr. Alan’s Shop; they are balanced by the horizontal lines of the lattice work and the provision tables in the bungalow. The scene is full of action in the exchanges between the market vendors and customers, and the crowds streaming in and out of Mr. Alan’s Shop. Colors are much brighter than in Daniel’s early works and underscore the dynamism of the scene. The painting reflects the ideal vision of an island society not yet overtaken by modernity. [Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Enid M. Baa Library, St. Thomas])

Images of Daniel’s art produced in the 1970s clearly show he was grappling with the clash of traditional values and contemporary life-styles: the alienation of the young and the generation gap, increased secularization and other “evils of materialism” threatening to destroy the fabric of society– labor unrest, crime, and anarchy. These may be some of his most powerful works; however, the last painting in Magda’s presentation, a self-portrait done in the 1950s, reveals Albert Daniel’s artistic capacity and complexity. Today he is regarded as a major voice in Virgin Islands cultural history, bearing out the artist’s own prediction: “When I am dust upon the wind, people will realize what I left behind.”

(Daniel said that he considered “Mass Hysteria” one of his deepest wood carvings. He stated: “In this carving I’m trying to express the agitation, the turmoil of the age we live in: man’s inhumanity to man.” — Here is one pushing another; a fallen man is crushed by others; some have given up the struggle. All figures are pressing on to the center with the slab of the war dead, above which a minister is preaching, unheeded by the crowd. The wheel of 1ife which represents the round of daily activities is caved in: the life of humanity is out of balance.” [Private collection])

Editors Note: Magda’s presentation was indeed remarkable and we all came away feeling how fortunate we are that people like Magda have the intellect, the energy, the enthusiasm and the vision to preserve aspects of the rich history of the islands and its people. Our heartfelt thanks.