Archeology in the Virgin Islands National Park

(A presentation by Ken Wild, summarized by Diana Hall)

Members of the St. John Historical Society present at the April 8 membership meeting learned that 2013 was an extremely productive year for the National Park Service Archeology Program as Virgin Islands National Park Archeologist and Cultural Resource Manager Ken Wild updated the audience on the program’s accomplishments. Wild, who graduated from the University of Tennessee and Florida State in archeology, is the Virgin Islands National Park’s archaeologist and cultural resource manager. In 2002, he received the National Park Service’s John Cotter Award for excellence in archeology for his work on St. John.

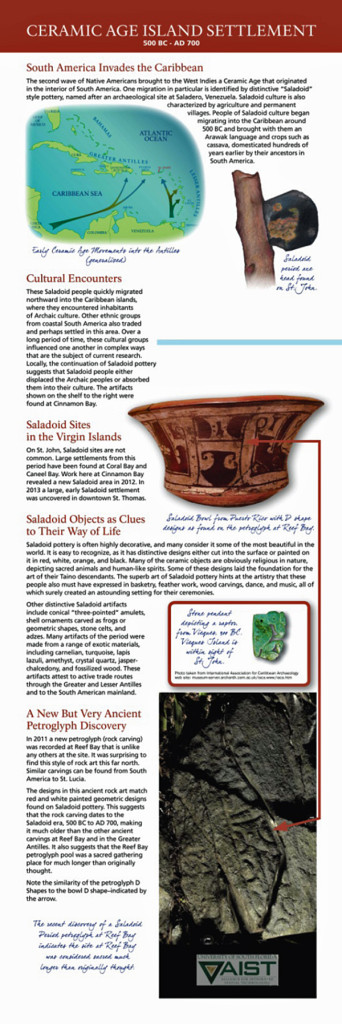

Wild informed the membership that early last year, the VINP received designation and funding for a rock art study that has allowed for 3D graphic imaging and analysis of the Reef Bay petroglyphs. This enhanced imaging technology brings forth details not always visible to the naked eye and resulted in the discovery of a new petroglyph at the Reef Bay site.

That alone would have been exciting for those interested in St. John’s ancient past, but according to Wild, the new petroglyph depicts a type of design associated with the Saladoid Period, placing it between AD 500 and BC 700. No previous example of rock art from this period has been discovered this far north, an indication that Reef Bay served as a sacred ceremonial site for pre-Columbian people much longer than was previously thought. Wild reported that the imaging and mapping project continues and that there is hope that more petroglyphs will be found.

In addition to the 3D imaging project, 2013 saw the completion of the ossuary at Cinnamon Bay, which provided for the re-interment of human remains that had surfaced due to beach erosion over many years. Bricks which had washed out with the remains were used to complete the ossuary cover, and there is a means to add additional remains as they wash out in the future.

Wild indicated that the project was undertaken in concert with State Historic Preservation Office and local clergy. The plaque on the ossuary reads, “Here lie the remains of individuals from Africa and Europe who lived, worked, and died here at Cinnamon Bay in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.”

At Francis Bay, Friends of the VINP archaeology funds were used to restore the last factory built on St. John. The NPS was able to use historical hinges, which went a long way in preserving the look and historic integrity of the project.

Wild also reported that with volunteer help, the site of a washout of human remains at the L’Esperance Plantation was stabilized and washed out remains were re-interred. Wild believes that, in keeping with the customs of the time, the remains at this site had previously been buried under the house.

An underwater survey was also undertaken in 2013 in the vicinity of Johnsons Reef, which is known to be a site hazardous to ship traffic. A proton-procession magnetometer and side-scan sonar were utilized in this mapping effort to identify undiscovered shipwrecks.

Those Society members who took advantage of the preview of the Museum at Cinnamon Bay on Saturday, April 12,were in for a treat. According to Wild, the exhibits at the Museum are being structured such that visitors will walk past cases of artifacts ordered chronologically to represent 100 to 200 year periods of time. Each case will contain materials and artifacts representative of St. John’s historic and prehistoric past.

“Teachers, students, and others will be able to move from case to case, walking through time,” said Wild.

The museum is a work in progress, said Wild, who reported that the glass panels that cover the cases have just been installed. Wild gave credit to the Friends of the VINP, indicating that the museum exhibits, the work of the interns, and the park’s volunteer program are all made possible through that organization’s fundraising efforts. Wild also credited Dr. Emily Lundberg for volunteering to edit the exhibit panels, Carlson Construction for the cabinetwork, and Kate Norfleet for her help with the exhibits’ design and layout.

Overall, there were 15,000 hours of volunteer time spent working on ruins and prehistoric sites in 2013. Fifteen elementary to high school groups toured the archeology labs and learned about the work being done there. Wild encouraged the Historical Society to take advantage of the resources of the archeology program and its interns and to schedule trips to project sites. Wild shared a photo of a high school student working with Chela Thomas, daughter of Paul Thomas, who earned a degree in biology but, according to Wild, has become “a wiz at cataloging all manner of artifacts.”

Wild reported on three projects the NPS archeology program undertook or completed on Hassel Island in 2013.

Federal funding was provided to restore the Hassel family cemetery which had been desecrated and looted, its graves left open to the elements. The monuments on site were completely restored by a local craftsman trained in historic restoration and knowledgeable in the use of historic materials using the appropriate lime mortar. . Wild cautioned that the use of the wrong materials can do a lot of damage and indicated his pleasure that the Historical Society is planning to utilize the skills of the same knowledgeable craftsman for its cemetery restoration project in Cruz Bay, which David Knight also reported on at the meeting. Wild showed a photo of the beautifully restored monuments at the Hassel Island site and promised that, given time, they will acquire the same patina associated with other historic monuments.

Also with funding from the Friends of the Park, the NPS Archeology Program continued a metal restoration project at Creque Marine, completing in 2013 the restoration of the steam and fuel tanks, carpentry tools, and large chains and rods that pulled ships up the railway. Wild told the audience that Hassel Island is believed to be the site of one of the oldest and largest outdoor maritime railways in existence. Restoring the site is a large undertaking, and Wild expressed gratitude for the private funding that has made the project possible.

Wild indicated that the clearing of vegetation allowed for the survey and mapping of all the British 1801-1815 fortifications on Hassel Island for the Historic American Building Survey. The use of large format cameras and 3D mapping technology for the mapping project will enable interested individuals to access the completed maps through the HABS/HAER and Library of Congress web sites. Structures of note, according to Wild, are the Hassel family home, the officer’s quarters, barracks, the battery, and the ordinance magazine building —several photographs of which Wild shared with the group. Wild also shared a photo of the Shipley garrison house, which was converted in the mid-1800s into a small pox quarantine station. Of later historic interest is the WWII degaussing station, used to make ships less magnetically charged, and therefore less likely to attract enemy mines.

Wild spoke about the significant impact of Creque Marine and The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company on the economy of St. Thomas and St. John, indicating that many St. Johnians came to work in this new maritime industry.

Wild completed his talk with a preview of a project that promises to reshape archeological thinking, not just relating to St. John’s ancient past, but to that of the Caribbean in general.

Many Society members will be familiar with the excavation work that was done previously in Cinnamon Bay and the fact that erosion and the probable loss of the site was the impetus for selection of the actual dig site, but Wild also shared that the 1780 Oxholm map of the area helped highlight the road area as particularly critical for preservation.

It was almost immediately clear to those working on the site just how well chosen the dig site was when an articulated (intact) turtle shell was uncovered a mere three inches below ground followed by an offering of intact closed bivalve shells, giving strong evidence that the site had remained previously undisturbed and had served as the repository for sacred ceremonial offerings.

Wild asked the group to consider what may have accounted for the intact nature of the artifacts. He hinted that the site’s location, under an Old Danish road, had played a key role. Wild suggested that the attributes of a road with no vegetation or plowing activity to disturb the artifacts, and the fact that the Taíno had not lived in the structure where sacred offerings were given were major contributing factors in the preservation of the site. Thus, centuries of undisturbed Taíno offerings with a distinct timeline to match were discovered. Wild believes the preservation and richness of the site make it unique in the Caribbean.

“Because of the undisturbed nature of the site, with each 10 to 20 cm in depth you go back 100 years,” Wild said.

He reported that carbon dating along with changes in the style and type of artifacts has proven to match this rule of thumb.

According to Wild, when archaeologists look at artifacts, in addition to the carbon dating, they try to understand the cultural changes that took place over time. He pointed out that, in the past, artifacts found on St. John were considered primarily within the context of other Virgin Island sites. Given the many remarkable discoveries at the Cinnamon Bay archeological excavation project, however, a widening of the areas of comparison for artifacts found in the Virgin Islands is justified and may lead to a new understanding of the historic connection between St. John and the rest of the Caribbean.

Axe Head found on St. John

For example, Wild pointed out that the excavation at the Cinnamon Bay site revealed many artifacts associated with Puerto Rico and of an artistic style very closely associated with the Dominican Republic and Haiti. He, along with other researchers, suggest that it is necessary to rename ceramic types found in the Virgin Islands that are identical to the larger islands in order to make regional comparisons.

A larger regional consideration may also give clues as to why the Cinnamon Bay site was abandoned in 1440 and another ceremonial site on St. Thomas in the Tutu area was abandoned at about the same time. The question must be asked: What was happening in the region that led to the abandonment of both sites?

Responding to a question from the membership, Wild said that migration patterns suggest movement up island from Venezuela but some movement from South America as well. Interestingly, and perhaps significant to migration patterns from South America, Wild told the group that excavation at the site had revealed two pieces of gold — one copper gold and a second that is nearly pure. In an archeological context, Wild indicated that is yet another very significant finding. He noted that a student will begin work this summer to identify a geographical source of the gold for his master thesis.

On balance, those members of the St. John Historical Society lucky enough to be present for Ken Wild’s talk were left with the impression that the Cinnamon Bay findings may well inform the study of Taíno culture and the ancient history of the Caribbean for decades to come.

![Petroglyphs at Reef Bay. [Courtesy Ken Wild]](https://stjohnhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/a-PastedGraphic-1-1024x581.jpg)

![Cinnamon Bay ossuary. [Courtesy Ken Wild]](https://stjohnhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/A-Cinnamon-Bay-image-300x219.jpg)

Greetings,

My Name is Annice Canton, I am a librarian with the University of the Virgin Islands and an outreach librarian with Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC). I presented at a meeting a year ago, with my colleague Mark Sullivan, and wanted to follow-up with whether or not St. John Historical Society is still interested in becoming a member or partner. If so please, contact me at acanton@live.uvi.edu or the email listed above. I look forward to hearing from you.

Annice Canton, Librarian, University of the Virgin Islands 340-244-9823