Dear Judge, … Margaret Braithwaite

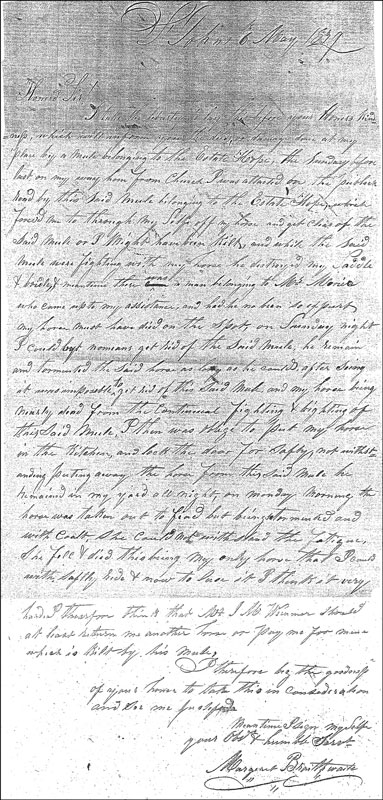

Margaret Catherine Braithwaite’s letter of complaint written to Judge (Landfoged) Johan Frederik Brahde on May 6, 1839. (Rigarkivet, West Indies Local Archive, St. John Landfoged [1741 – 1910], Entry 30.1)

So, let us now begin with a perfect case in point: a hastily-scrawled note of complaint written by one of St. John’s most intriguing colonial inhabitants, Margaret Catherine Braithwaite. According to the “1832 Register of the Free Colored Inhabitants of St. John,” Margaret Braithwaite was born into slavery on the island of Tortola in 1762 (although the 1860 census of St. John gives her place of birth as “Africa”). In 1797 she was brought to St. John by the owner of Estate Bordeaux, Reverend Thomas Braithwaite, who had purchased her freedom on the 27th of May of that year. Over the course of their relationship Margaret produced three children with Thomas Braithwaite, all girls, who were left sizable “fortunes” upon the good Reverend’s demise. After Thomas Braithwaite’s death Margaret was displaced from Estate Bordeaux, but soon found an agreeable situation as the paramour of St. John Landfoged Louis Michel, the owner of estates Hope and Misgunst. Louis Michel died in 1838, leaving Margaret and their daughter, Catharine, a 10-acre parcel of Estate Misgunst, on which stood the former estate residence and the ruins of a sugar works.

And so it is here, living on her newly-inherited property atop a rugged knoll overlooking the Reef Bay valley, that we encounter 77-year-old Margaret Catherine Braithwaite, mistress of Estate Misgunst, in a state of great consternation:

St. John 6th May, 1839

Honerd Sir!

I take the liberty to lay this before your Honers Kindness, which will inform you the deeds or damage done at my place by a mule belonging to the Estate Hope, the Sunday before last, on my way home from church. I was attacked on the publick road by this said mule belonging to the Estate Hope which forced me to through my self off my horse and get clear of the said mule or I might have been Kilt, and while the said mule was fighting with my horse he destroyed my Saddle & bridle, & meantime there was a man belonging to Mr. Morier who came up to my assistance, and had he not been so expert my horse must have died on the Spot, on Sunday night I could by nomeans get rid of the said mule, he remain and tormented the said horse as he could, after seeing it was imposible to get rid of the said mule, and my horse being nearly dead from the continual fighting & bighting of the said mule, I then was oblige to put my horse in the Kitchen, and lock the door for safty, not withstanding putting away the horse from this said mule he remained in my yard all night, on Monday morning the horse was taken out to feed but being so tormented and with Coalt, she could not withstand the fatigue, She fell & died this being my only horse that I could with safty ride & now to lose it I think it very hard. I thearfore think that Mr. J. W. Weinmar at least return me another horse or pay me fore mine which is Kilt by his mule.

I therefore beg the goodness of your honer to take this in consideration and see me justified.

Meantime I sign myself Your Obdt. & humble Servt.

[signed] Margaret BraithwaiteNote: to the best of my ability the accompanying transcript of Margaret Braithwaite’s letter has been copied verbatim; there has been no attempt to correct spelling or punctuation. While Margaret’s language and spelling may seem odd to the modern reader, when one puts excepted norms aside the true voice and dialect of a 19th century resident of St. John is vividly revealed. Given her background and the context of the period, especially when compared against her contemporaries (of both European and African heritage), Ms. Braithwaite’s written communication skills are truly astonishing.