Vaniniberg Estate Hike

(Presented by David Knight and Eleanor Gibney Summarized by Robin Swank)

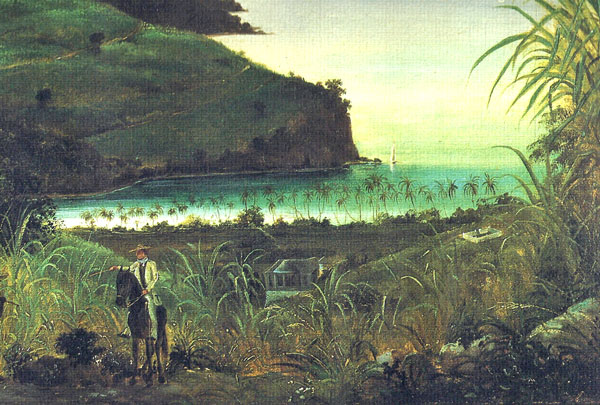

Maho Bay and the Vaniniberg Estate House. Detail from a painting by Fritz Melbye, c 1852, of Maho Bay

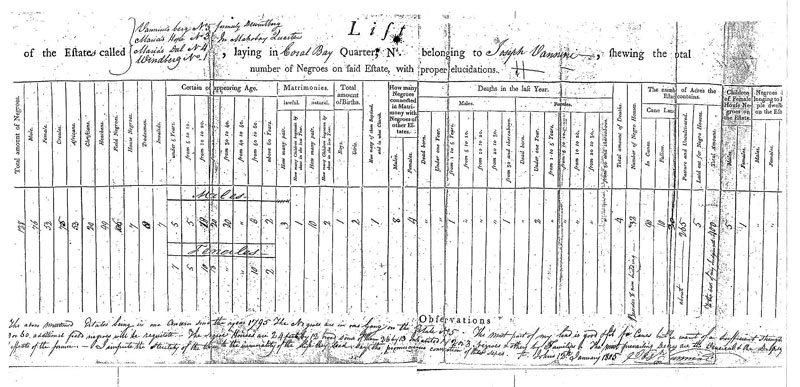

Three dozen hikers attended the last SJHS event of the 2009-2010 season – an engaging trek to Estate Vaniniberg. The tour of this little-known and little-documented colonial estate was led by historian David Knight and botanist Eleanor Gibney. Vaniniberg, David tells us, was formed by merging a number of estates during the late-1700s sugar boom, when inflated sugar prices made the planting of smaller and more difficult acreages profitable, a time when newcomers bought up abandoned or bankrupt properties and rebuilt them. This pattern began in about 1779, although it was short-lived; by the mid-1820s, the sugar boom had gone bust. Joseph Vanini erected his estate over the footprints of older buildings, installing additions and upgrades that represented the peak of 1700s’ sugar-and rum-making technologies. Vaniniberg was the result of combining Estates deWintberg, Maria’s Hope, and Mariadahl from Maho Bay Quarter, and Estate Windberg (AKA Windy Hill), which according to tax rolls, was Parcel #1 in Coral Bay Quarter. It is most likely, David conjectures, that deWintberg and Windberg have been erroneously considered variants of the same estate name in the past, because historians weren’t looking across multiple Quarters’ records. However, Joseph Vanini’s formation of his estate is clearly documented in numerous primary resources as a consolidation of these four parcels. See the 1805 Census below.

Image of the 1805 Census of the Estates belonging to Joseph Vanini. (Image courtesy of David Knight)

Our hike begins at the north end of Maho Bay, near an old oven and an 18th century warehouse close to the beach. The oven sits fairly intact in the space now designated for Maho Beach parking. Composed of recycled generations of yellow and red brick, it doesn’t seem to include any mid-19th century firebrick, which suggests that the structure was built prior to that time. It may have been in use, however, up until the 20th century. Unlike the mid- to late-1700s era warehouse and loading platform on the north side of the current road, the oven is not listed on the extensive Vaniniberg inventory. Some of our members may recall the warehouse as the home of Aegis Marsh, who, living on one of the largest flood plains on St. John, often escaped the evening’s no-seeums by sitting in the sea up to his nose. We proceed eastward and uphill on the North Shore road. To our left, we pass segments of old retaining walls with weepholes, and layered debris containing whelk shells and lime mortar, which would have packed the floors of the houses in the laborers’ village. Probably over 100 slaves lived between the warehouse and the current Y where two one-way roads diverge. Eleanor calls our attention to the landscape’s composition, primarily small genip trees and a tangle of thorny catch ’n’ keep — genips being common during the colonial era as community trees in laborers’ villages, and catch ‘n’ keep being a vestige of past livestock grazing. These slopes were grazed by Aegis Marsh’s cattle up until the 1970s. Soon we encounter the chimney of the Vaniniberg sugar factory located immediately next to the road. There may have been a sugar works on this site as early as the 1720s; but both the chimney and boiling house that stand on the site today appear to have been built by Peter deWindt in the 1780s, utilizing the most modern technology of his era. Later the factory was rebuilt and upgraded by Joseph Vanini, who invested huge sums of money to expand both the land area and production capabilities of the estate at the beginning of the 19th century. The chimney was probably many times taller than its ruins today—in this low valley we assume it must have required more height in order to draft properly. As a result of its being rebuilt over the same site, the existing factory complex has elements of both the old and new upgrades. The chimney is built of both mid- to late-1800s firebrick, as well as 1700s rubble. The sugar factory, concealed by heavy bush behind the chimney, shows the location of an original set of sugar kettles as well as a set of kettles that Vanini added to increase capacity. Vanini also added a second pot still, which facilitated double distilling to produce higher quality rum, a technological upgrade of the time. A little farther down the road we also pause at one of the most beautiful photo ops of the trek, a water receiver, which is a relic of the estate’s water management system. The structure is double arched for strength to support a holding tank for fresh water, captured by a reservoir in a dammed –up gut about 1000 feet above the factory. The water was conveyed to the works by gravity through a stone and tile-lined aqueduct with wooden extension channels. David points out that a reliable source of fresh water was essential to both successful sugar manufacturing and the production of high-quality rum. From our location, we can see the huge, once cleared expanse of watershed that would have fed the reservoir. Eleanor informs us that she has never seen the Vaniniberg gut entirely dry. The rather sophisticated water management system at Vaniniberg probably used removable lead-lined wooden runnels to channel fresh water from the receiver tank to other areas of the factory. Whereas on flat landscape, an estate might have had to create elevation for this gravity-fed water delivery capability (as in the cases of the pump and well-tower systems at Frederiksdahl and Leinster Bay, or the use of a “water wheel” at Browns Bay), Vaniniberg’s hilly topography is clearly taken advantage of here, making use of natural elevations to heighten efficiency and save manual and animal labor.

A buttress to support the gallery of the expanded Vanini estate house is now peeling away from the original wall. (Photo courtesy of Linda English)

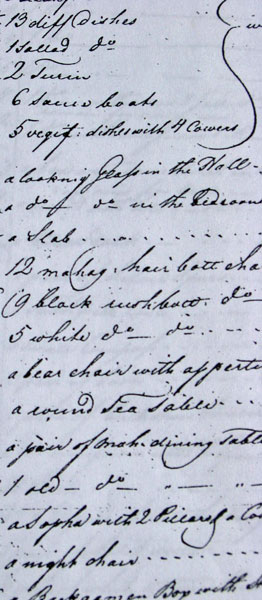

Now that the hikers are spoiled by the easy accessibility to this estate’s factory from the paved road, Eleanor and David lead us off-road through the sugar crushing mill and platform, past the old boiling house, and on a climb through the catch and keep to the estate house. The house followed the tradition of its time—it was placed at a location from which an owner could view all of his holdings and assets. From its now overgrown location, you can’t see the stand of white mangroves on the flood plain, but you can imagine the cultural landscape of yesteryear, evidenced by thinly-covered hills. It will take perhaps 80 years, estimates Eleanor, for the landscape to revert to true “forest island” status. Vanini’s was a large and opulent household. The house had an outer wall, and Vanini added a gallery off the front of the older house. The gallery expanded the house dimensions from 32 by 66 feet, which was its size in 1781, to 32 by 72 feet, and at some point it was necessary to construct an impressive rubble-masonry buttress to support the gallery’s massive downslope foundation. In 1806 the house was valued at 8500 Rigsdaller (Rd), up considerably from Vanini’s purchase date, when it was valued at 4000 Rds. Vanini’s ownership of the estate was short. At his wife’s death in 1806, he was required to mortgage the property heavily. When he died in 1811, his heirs (2 daughters and his wife’s mother in London—all of whom were owed proceeds from previous years), the holders of his mortgages, and his trading partners to whom he owed monies, called for the property to be sold at auction to pay his accumulated debts, which amounted to over 200,000 Rd. The map of Vanini estates procedure and subsequent estate auction resulted in one of the most spectacularly detailed inventories ever recorded from this period. Vanini’s auction list alone provides us with insights into the life of an enigmatic early 19th century planter on St. John, who otherwise left very little documentary evidence to speak of his brief presence.  Vanini was most likely a retired or active British military officer. David tells us that the family name figures prominently in British military history and he reminds us that St. John (as well as other Danish West Indies islands) was twice occupied by the British during Vanini’s residency—first from 1801 to 1802, and then again from 1807-1815. In addition to the “red uniform with 2 epaulettes,” and a “military hat with four feathers,” the complete set of “Waydons” pistols in a case, and swords with belts and “notts,” Vanini’s household inventory includes “2 iron canons with carriages,” (possibly to ward off non-British pretenders during this time of the Napoleonic wars?) and a “stone watch house on the bay, fireproofed..” This last item may have been a fire watch house to provide escape while the fields were being burned to clear, or simply related to the “at war” state of the British colonists. (Partial Auction List for the estate of planter Joseph Vaninni of Vaninniberg October 1811 (formerly, estates deWintberg, Maria’s Hope, Mariadahl (#5, #4, #3 in the Maho Bay Quarter) and Windberg (#1 in the coral Bay Quarter). The listing of household goods by the estate manager, Owen Brown, showed that he was probably valued for his thoroughness as well as his knowledge of sugar and rum production. The Inventory in its entirety can be viewed on the SJHS website. Other buildings inventoried include “a storehouse on the bay with boarded platform,” “28 negro houses” (which housed the estate’s 123 slaves), the mill and all the factory accoutrement for rum, molasses, and sugar making. A shingled “magasse house” (which would have stored the spent cane stalks and kept them dry to use as fuel), and the “Water Receiver over the worm cistern and 3 liquor spouts,” are listed. Structures that have probably since aged off the landscape are also inventoried and include a “sickhouse with three chambers,” common to most large plantations in the “ameliorative period,” when living conditions for valuable slaves became more important as the slave trade was abolished. Post-abolition sugar production required the slave population to thrive, notes David. This estate could have hosted large dinner parties, as the inventory of place settings and dinnerware includes a dozen horsehair chairs, a pair of mahogany dining tables, two full sets of china, and 8 dozen wine and water glasses. The gold and silver, silver plate, games, instruments, clothes, linen, furniture, livestock, tools, liquor, boats, and the estate’s provisions and supplies—right down to the number of red oak barrel staves and horseshoe nails appear in detail, presumably each as a separate lot for auction. Even “4 forms of clayed (white refined) sugar,” which would have been purchased from Europe, as the making of refined sugar was illegal in the colonies, are itemized. The enslaved population is also listed. The 7 “mackaroons” (sic) (older or infirm, and therefore untaxed, slaves) include Jonas, who was listed as a “Doctor.” There is also a woman listed as “Nurse.” Twenty-three children, 8 tradesman, 8 house servants, 46 men and boys, and 33 women and girls are enumerated by first name, and in some cases by their trade or other distinction.

Vanini was most likely a retired or active British military officer. David tells us that the family name figures prominently in British military history and he reminds us that St. John (as well as other Danish West Indies islands) was twice occupied by the British during Vanini’s residency—first from 1801 to 1802, and then again from 1807-1815. In addition to the “red uniform with 2 epaulettes,” and a “military hat with four feathers,” the complete set of “Waydons” pistols in a case, and swords with belts and “notts,” Vanini’s household inventory includes “2 iron canons with carriages,” (possibly to ward off non-British pretenders during this time of the Napoleonic wars?) and a “stone watch house on the bay, fireproofed..” This last item may have been a fire watch house to provide escape while the fields were being burned to clear, or simply related to the “at war” state of the British colonists. (Partial Auction List for the estate of planter Joseph Vaninni of Vaninniberg October 1811 (formerly, estates deWintberg, Maria’s Hope, Mariadahl (#5, #4, #3 in the Maho Bay Quarter) and Windberg (#1 in the coral Bay Quarter). The listing of household goods by the estate manager, Owen Brown, showed that he was probably valued for his thoroughness as well as his knowledge of sugar and rum production. The Inventory in its entirety can be viewed on the SJHS website. Other buildings inventoried include “a storehouse on the bay with boarded platform,” “28 negro houses” (which housed the estate’s 123 slaves), the mill and all the factory accoutrement for rum, molasses, and sugar making. A shingled “magasse house” (which would have stored the spent cane stalks and kept them dry to use as fuel), and the “Water Receiver over the worm cistern and 3 liquor spouts,” are listed. Structures that have probably since aged off the landscape are also inventoried and include a “sickhouse with three chambers,” common to most large plantations in the “ameliorative period,” when living conditions for valuable slaves became more important as the slave trade was abolished. Post-abolition sugar production required the slave population to thrive, notes David. This estate could have hosted large dinner parties, as the inventory of place settings and dinnerware includes a dozen horsehair chairs, a pair of mahogany dining tables, two full sets of china, and 8 dozen wine and water glasses. The gold and silver, silver plate, games, instruments, clothes, linen, furniture, livestock, tools, liquor, boats, and the estate’s provisions and supplies—right down to the number of red oak barrel staves and horseshoe nails appear in detail, presumably each as a separate lot for auction. Even “4 forms of clayed (white refined) sugar,” which would have been purchased from Europe, as the making of refined sugar was illegal in the colonies, are itemized. The enslaved population is also listed. The 7 “mackaroons” (sic) (older or infirm, and therefore untaxed, slaves) include Jonas, who was listed as a “Doctor.” There is also a woman listed as “Nurse.” Twenty-three children, 8 tradesman, 8 house servants, 46 men and boys, and 33 women and girls are enumerated by first name, and in some cases by their trade or other distinction.

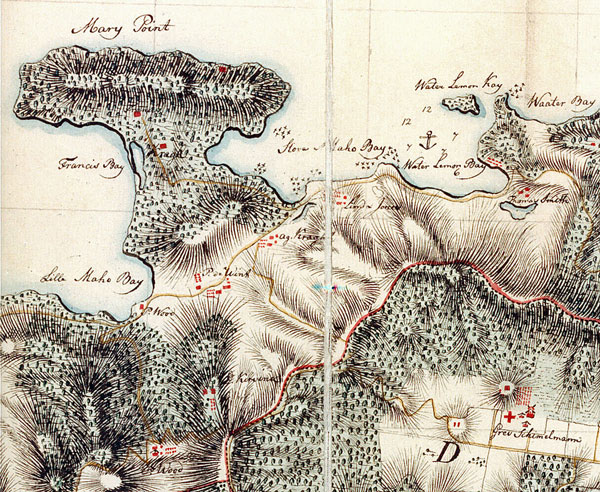

On Oxholm’s map, “P. deWint” signifies deWintberg; “D.Kervink” signifies Windberg, aka Windy Hill; “P.Wood “ on the Bay is Mariadahl; and “P. Wood” at the head of Reef Bay trail is Maria’s Hope. The totality of this real estate is Vaniniberg. Adding Age.Kragh, neighboring P. deWindt to the northeast, (this is Frederiksdalh and Frederiksberg, aka Munsbury) to Vaniniberg, later yields Abraham’s Fancy.

The entire Vaniniberg property was bought at auction by Abraham C. Hill of Tortola, who also purchased neighboring Munsbury from James Murphy’s probate. With these acquisitions, Hill created the huge sugar estate that he christened Abraham’s Fancy,” a property composed of 7 formerly independent plantations: deWintberg, Windberg, Maria’s Hope, Mariasdahl, Frederiksdahl, Frederiksberg, and a portion of Betty’s Hope. At that point the former Vaniniberg estate house was apportioned to the use of Hill’s overseer, while Hill built a grand new estate house, named “Mount Pleasant,” situated on the steep slopes of Frederiksberg and overlooking his vast domain. Thank you, David and Eleanor and hikers, for the good information, good questions, and good company. MODERN POSTSCRIPT-The Hill family kept Abraham’s Fancy for some 90 years, and eventually sold it to Ernest Marsh in about 1900. The Marsh family heirs sold a 4/11th undivided interest to the V.I. National Park in the 1960s, and the Trust for Public Land acquired six of the remaining 7/11th s for the Park in 2009. All the lower hills were kept clear-cut for grazing through the 1970s, Eleanor reminds us, and until quite recently, there was still a cattle guard across the road.