Masquerade – Costumes of the Atlantic Rim

(By Dr. Robert W. Nicholls, Summarized by Robin Swank)

Yet another reason to attend our St. John 4th of July Carnival parade!

At our April membership meeting, Dr. Robert Nicholls told us the history of some of the characters parading at Carnival. He urged us to think of the entire Atlantic Rim as a region in which ‘masquerade’ or ‘mas’ arose based on the availability of practical materials. He then asked us to think of it as an arena of cultural diffusion. With written references and extraordinary images from centuries ago through modern times, he demonstrated how the Atlantic Rim Region (West Africa, the Caribbean, Western Europe, and the American seacoast up to Newfoundland) probably shared its ‘mas’ character development.

Dr. Robert Nicholls’ Old Time Masquerading

in the U.S.Virgin Islands, published in 1998, is

available from the Virgin Island Humanities

Council. You will also find him regualrly

featured in the seasonal Saint Thomas Carnival

publication; his articles provide rich references

and bibliographies, and wonderful photographs.

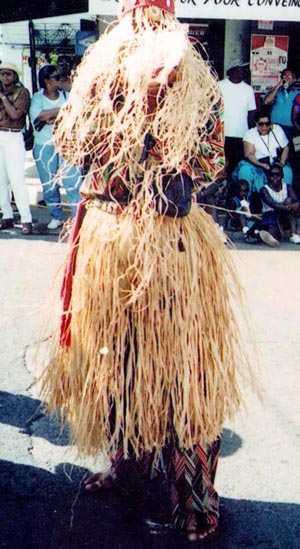

West African Masquerade, he begins, was spiritual. The idea was not to see or be able to identify the human being; the flesh is concealed. This tradition carried over to the Caribbean to a large degree, but has weakened over time. Performers today tend to enhance, rather than to disguise their human attributes, creating, says Dr. Nicholls, ‘promenading’ rather than true ‘masquerading.’ Authentic mocko jumbies, e.g. still wear masks, and a traditional clown wears gloves, a full-face screen mask, and a full head-covering including a stocking cap to cover his ears and the back of his neck. But for the most part, the identity of the human participant has become more apparent in today’s Carnival parades. In a modest change, face paint might be used rather than a mask. On extremely modern non-traditional participants, you might need to look very hard to find a remnant of ‘mas’ covering any part of a person.The ‘creolized’ masquerade prototypes emerged, as did the creole dialect, at the beginning of the plantation economy. At that time, ‘mas’ traditions and characters came to the Caribbean from West African and European antecedents, notably the Upper Guinea Region including Ivory Coast to Senegal, and Britain’s West Country including Cornwall, Gloucestershire, and Dorset Counties. In the Virgin Islands, as elsewhere, masking was an aspect of a larger range of activities, including seasonal holidays, such as Easter, Whit-Monday, May Day and the Christmas-New Year-Three Kings’ Day period. In the 19th century, the Caribbean styles and costumes crossed back to coastal Africa. Dr. Nicholls showed us extensive pictures of several masquerade ‘types’ with roots from both sides of the Atlantic rim.The RAFFIA masquerade covers the body, creating the shaggy monster look. It is made of dried shredded vegetal material, widely available. The costume probably developed in parallel in several geographic regions– we saw images of a featureless raffia masquerade from the Igede of Nigeria, and an Austrian ‘besom’ (old fashioned broom) character with the handle dancing from its head. We also saw a ‘straw bear’ from an 1886 English Christmas/New Years event, an image of a 1980 Frederiksted straw bear representing the early straw bears of Barbados and the VI, and a 2005 image from the St. Thomas Carnival of a very folksy costumed ‘bear’ with an ET plastic face!

Raffia Masquerade in Frederiksted

(photo from “Avis”)

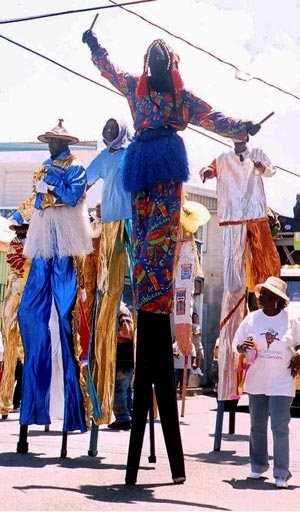

Early SHE-MALE costumes were readily available and therefore relatively inexpensive. The concept of men dressing as women, and vice-versa, is not new; in the sixth century, says Dr. Nicholls, there are accounts of French clerics complaining about it. One well-known buxom Virgin Islands she-male was The Tantalizer, or Tanto Liza, about whom the following was sung: “Tanto Liza gone, gone; he gone to the jailhouse.” Meanwhile in England, the Monkseaton Sword Dancer appears as a she-male; and we see additional she-males in the Caribbean tradition from Sierra Leone. From the west side of the Atlantic Rim, we also saw an 1836 image of Kuku the Actor Boy from Jamaica, female representation at a grand level. These later costumes are intricate, expensive and not at all solely pragmatic, as was the earlier incarnation.The supernatural scarecrow, the MOCKO JUMBIE, is now the quintessential Caribbean masquerade character. And it has a long history in the Caribbean. It is likely that mocko jumbies derived from stilted dancers of the Dan from the Ivory Coast or the Kono of Guinea. In St. Vincent in 1791 Williams Young saw a ‘mocko jumbo’ on stilts, with a fake head on top of the actor’s head. A line drawing of a stilt dancer entitled ‘Mocha jumpy-Christmastime’ dated 1871 by the Danish National Museum, depicts a pale-masked man in female dress of petticoats and flounces, flipping them to keep away the evil spirits. In 1917, Dr. Nicholls tells us, Thora Visby-Petersen wrote of masquerades she saw in St. Thomas in 1892. She describes a ‘traditional Mumbo Jumbo,’ or ‘Mukke Jumbe,’ and she stated the bogeyman was always performed by a man dressed in women’s clothing.We saw an image of well known mocko jumbie Magnus Farrell in his triangular hat on St. Thomas in 1950. Along with more money, female dress was jettisoned and the more expensive costume of long leggings to accommodate the 12 foot stilts, African style clothes and gloves came into being.

She male in St. Thomas Carnival.

(Photo from the Daily News)

BULLS, with raffia bodies and wire screen masks or blackened faces, populate early accounts of the 17th and 18th centuries in the Caribbean. A ‘John Connu’ with bull horns, e.g., was documented in Jamaica in the 1760’s. In England there are few photos but many written reports of ‘bullocks’ in Scotland and Cornwall during the 12 days of Christmas when ‘guise’ dances were performed; from the 6th century onward, the Christmas Bull is mentioned in France, Spain, Britain, Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. The bull waned following the Reformation, but he returned in Britain and the BWI’s almost simultaneously, although a link is difficult to document.We saw an image from the 1930’s of a mask with real horns; masks with real bull horns feature in the initiation rituals of various Mande speaking peoples in the Upper Guinea region and were described as early as the 17th century. However, real horns are rarely used in West Africa; more commonly they are carved in wood. In the VI, in one imaginative approach, spools were used. The Bull often wore a padded burlap shirt to foil the whipman who accompanied him.

Mocko Jumbie, the quintessential

Caribbean masquerade.

(Photo by Dr. Robert Nicholls)

Why bulls? Peter Mark in his 1992 The Wild Bull and the Sacred Forest maintains that Mandinka bull masks contain symbolic reference to the slave trade, because slaves were purchased or ransomed using cattle as currency within the region. Buffalo horn headdresses were also worn in NE Ghana; to kill a wild buffalo was symbolic to manhood. The bull was fairly widespread in the Caribbean. Although he ‘died out’ in the 1950’s he is making a re-emergence.CLOTH COSTUMES of flour and chicken feed sacks festooned with ribbons probably arose when money was scarce. Pitchy Patchy is perhaps the most well-known of these characters. We also saw a Dominican ‘sensay mas’, representing the duppy-catching ‘frizzled feathered chicken’, prized for its ability to find and scratch out evil. Possibly derived from the raffia masquerade styles or early cloth West African styles, the Caribbean cloth costume versions looked quite similar to the English ones. Images of West Indian Pitchy Patchy mas characters and of British mumming costumes like those of the Marshfield Paper Boys (who used paper strips instead of cloth ones) from Glocestershire, England show how unlikely parallel evolution was – who influenced whom is still an open issue.

John Bull in Antigua

(Photo by Dr. Robert Nicholls)

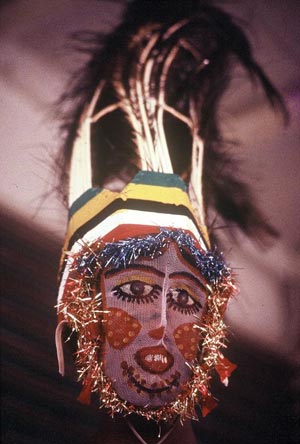

WIRE MESH, starched cloth or sometimes the dried and lacquered skin of an oldwife fish (Balistes vetula) were used to create wire masks. Wire mesh masks are known in the Virgin Islands as ‘safe wire’ masks, because the wire gauze was the same as that used for food safes before refrigerators were available. Wire screen masks were practical and the material readily available; they allowed one to breathe, see, and they protected one’s face. Annie Sidro, who wrote Carnival in Nice, The World and I: A Chronicle of our Changing Era, explained that in 19th century carnivals in Nice, flower petals, candy-sugar confetti, plaster, and baker’s flour were liberally thrown around. This also occurred in the Virgin Islands.

Pitchy Patchy is a masquerade whose

costume is covered with strips

of colored cloth.

(Photo by Dr. Robert Nicholls)

Dr. Nicholls shows us, from the other side of the Atlantic Rim, a Kono stilt masquerader wearing a net mask made of palm tree fiber; a 1914 image of both men and women wearing masks at a ‘coming out ’(to masquerade) at Christmas; then a Mother Hubbard and other masked figures. According to the late Rufus Vanderpool, Dr. Nicholls tells us, some masks were commercially made and imported from Europe. In his 1996 book Carnival, Canboulay, and Calypso, Traditions in the Making, John Cowley reproduces a 1901 Trinidad newspaper ad for ‘wire masks; by the gross, by the dozen, or by a single one.’Historically masks could be pink with blue eyes representing Caucasians, white or pale representing white or colorless spirits, or featureless and faceless black netting, which heightened the mystique of the masquerade.

Wire Mesh masks are worn by clowns

in the VI, the Highlanders in Antigua,

Jonkonu in Belize, and in this photo by

Dr. Robert Nicholls, in a St.

Kitts-Nevis masquerade.

How often has there been cross-cultural diffusion of ‘mas’ costuming? There is lots of rational speculation, but little proof. In 1967 J. Kedjanyi speculated that British West Indian troops of African and Caribbean descent, brought to Africa by the government of Sierra Leone in 1822, brought with them their cultural ‘mas’ traditions. Sailors from Liberia and Ghana probably spread these ‘mas’ styles along the coast of Africa. Looking historically at the costuming on both sides of the Atlantic Rim over time, it is easy to see both instances of local invention in the use of materials, and instances substantiating Dr. Nicholls’ hypothesis of repeated cross-cultural diffusion at play.This July 4th, look out for old, evolving, and new characters in our St. John Carnival parade. And if you find one you like, be sure to take a picture to document another appearance of a far, wide and long-standing expression of human celebration. Thank you, Dr. Nicholls; we’ll see you at the Parade.

See the related items:

[Way of life]