Of Waterfalls and Rock Carvings… Excerpted from THE VIRGIN ISLANDS Our new Possessions and the British Islands

By Theodoor deBooy and John T. Faris (1918)

…There is no road on St. John that is more than a bridle path; but also let it be said that there is no road that does not have features to delight the visitor. The road most commonly used by the inhabitants leads from Cruz Bay through the center of the island to Emmaus, and from there to the East End settlement. Directly after leaving the Cruz Bay landing one ascends the hill, passing, in turn, Herman Farm with its extensive ruins, and Adrian, another forgotten plantation which is almost entirely obliterated by the jungle. At Esperance a road branches off to the south coast and to Reef Bay. This branch road leads over the summit of Camel Mountain, the highest peak on the island, and then dips toward the sea at a precipitous angle.

Some half mile inland from the shores of Reef Bay one obtains a distant glimpse of the Reef Bay waterfall. A searching glance is necessary, as it is hard to make out the thin thread of water that comes tumbling from the heights above. The rocks back of the waterfall are plainly to be seen, however. It is said that this waterfall is never dry. Occasionally it becomes so small as to be almost negligible, but it never seems entirely to vanish. One is privileged to surmise, therefore, that in pre-Columbian days, when the woods of the island were still intact and fulfilled their purpose in drawing water from the clouds, the volume of water passing over the rocks must have been considerably larger.

There are in reality two falls, but the higher fall is difficult of access. The lower fall is about forty-five feet high. As the crow flies, it is not over one and a quarter miles from the sea and not more than half a mile from the road. In order to visit it, it is necessary to follow a dried-up watercourse, and then cut a way through a some–what dense thicket. Before the hurricane of October, 1916, there was a small footpath following this water course, and the ascent to the falls was far easier than it is today.

The lower fall empties itself into a pool some five feet deep and about twelve feet in diameter. This pool empties its contents into a second pool about seven feet lower than the first. The second pool, in which the water is quite tranquil, is about six and one-half feet deep, fourteen feet wide and nine feet broad, and makes an excellent bathing place. The water, filtered during its long passage through the hills, is excellently adapted for drinking purposes, and it is possible that the Indians inhabiting the south coast of St. John must have come here for their supply of drinking water.

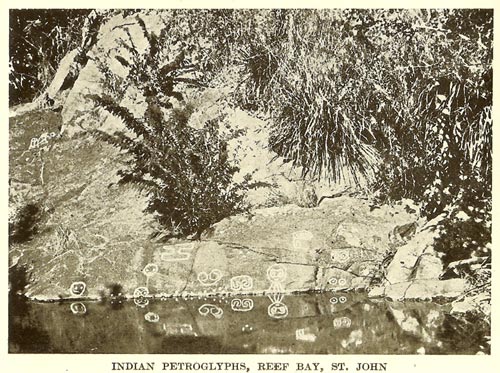

Around this pool, in which bathing is a pleasure—a cold pleasure—one finds huge boulders upon which are more of the aboriginal carvings known as petroglyphs.

There really are three sets of rock carvings on the stones surrounding the pool, and it is impossible to get all three sets in one picture. The most elaborate set is found just above the edge of the pool and the Indians seem to have designed the carvings so that their reflection would show clearly in the water. A few of the figures seem to depict a very crudely drawn human face, consisting of a circle for the face, with smaller circles or just dots for the eyes, and a line for the mouth. In one or two instances some extra lines below the large circle may represent arms and legs. But the reader is at liberty to scoff at this suggestion. The largest figure of all, in appearance somewhat like a figure eight, or like a sand glass, is perhaps the most inexplicable.

In order to give one some idea of these carvings, it may be said that from the figure on the extreme left side of the rock, just above the water line, to the figure on the extreme right hand side, just above the water line, is a distance of ten feet four inches.

On the same large rock, a little to the left, but at a much higher point above the pool, one can find another series of petroglyphs even more enigmatical than those just above the water level. This group consists of six figures, two of which represent somewhat simply designed human forms strongly reminiscent of the pictures chalked by children on wooden fences and two simple faces.

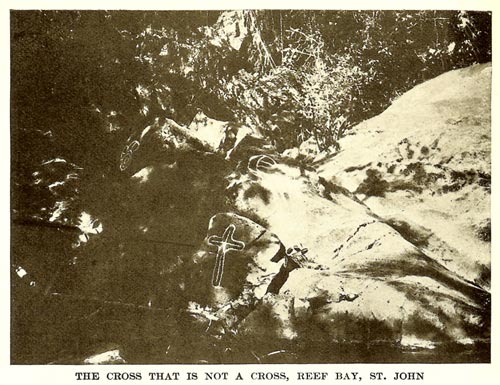

On the extreme western side of the pool is another rock upon which are seen three more carvings. This rock may well be named the “Archeologist’s Delight.” No doubt every person who ever has seen it, excepting of course the original Indians, has evolved some deep theory regarding the carvings on this boulder. Almost any meaning may be given to two of the three figures. The one on the extreme left of the photograph and the one directly above the carving that looks exactly like a cross. It is therefore possible to eliminate two carvings at the very start, which is far more than would be done by seriously minded amateur archeologists who would deem it their duty to explain fully these two problematical carvings.

But there still remains the crosslike figure. Can it be that the teachings of Christianity had penetrated to the New World before the discovery of St. John and the Virgin Island group in 1493? This is to be doubted. Then were the Indians converted to Christianity by the piously inclined conquistadors? Considering that these same conquistadors were responsible for the total extermination of the Indian race some thirty years after the discovery of the West Indies, this also is to be doubted. Then why the cross? Perhaps the most ingenious explanation is the one found in an early history or the Danish West Indies in which the author states that the Spanish monks saw the other carvings on the rocks and deemed them to be the work of the Devil. In order speedily to overcome the evil influence, the earnest friars carved the sign of the cross on the rock, thereby neutralizing all other influences.

But the carving of the cross appears to be of the same age as the other figures on the same rock. And the suggestion is made that the sign of the cross has been found in many places to which it is positively known that Christianity never penetrated. Yet the sign is there, and has been found in many forms, perhaps one of the most common of which is the swastika sign. This sign represents nothing more than the four cardinal points of the compass, east, south, west and north, and by a process of evolution first became a figure resembling two interlaced S figures and finally a simple cross. But when challenged on the subject, we must withdraw this explanation of the cross figure at Reef Bay. The carving representing the cross stands seventeen inches high, and the length of the cross arm is eleven inches.

It is time to turn from the mysterious petroglyphs and follow the south coast, by Parforce Estate…

See the related items:

[Natural history]

| Resource | Title | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Article | Bay Rum: A Niche of Distinction in VI History | Schulterbrandt, L.D.N., Gail |

| Article | Forest Island | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Soldier Crab Saga | Boulon, Rafe |

| Article | Nineteenth Century Ornithologist at Estate Adrian | Ober, Frederick |

| Article | Report of the Earthquake of 1867 | Housel, Louis van |

| Article | November Rain | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Of Waterfalls and Rock Carvings | deBooy, Theodoor and Faris, John T. |

| Article | Earth Day 2008 on the SJHS Provisions Grounds | Schoonover, Bruce & Swank, Robin |

| Article | Hike to Estate Retreat | Swank, Robin |

| Article | Earthquakes & Tsunamis: Prospects for the Virgin Islands | Watlington, Roy and Lincoln, Shirley |

| Article | Lignum vitae: Beauty, Strength, and the Fallibility of Medicine | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Fever | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Historical Society Installs Plant Signs at Annaberg | Schoonover, Bruce |