Lignum vitae Beauty, Strength, and the Fallibility of Medicine

Most people who have spent any real amount of time in the West Indies are at least vaguely acquainted with the small tree known as lignum vitae—a Latin name meaning “wood of life”, but oddly enough, NOT the tree’s scientific name: that would be Guaiacum officinale— from the Taino name guayacan, and “officinale” meaning official, or prescribed in pharmacy. Early setters in these islands called it buckwood, pockwood and sometimes frenchwood (for reasons we’ll later reveal), and Virgin Islanders have often pronounced the Latin with a certain softening: “lingy whitey.”

Apparently lignum vitae was a major species in original dry forest of the Virgin Islands. The Buck islands, off both St. Croix and St. Thomas, the island now called Le Duck off Coral Bay (once Bocken Island), and the area known as Pockwood Pond on the south shore of Tortola were all named from the former abundance of this tree.

Real St. John lignum vitae is a south shore species, still found in the wild from Chocolate Hole to Round Bay. There are probably more lignum vitaes in island gardens now than are left in the wild, although St. John has far more wild trees remaining than any of the other Virgins. These islands are pretty much smack in the middle of the tree’s natural range, from the Bahamas to Venezuela. Over-harvesting certainly led to the species becoming rare or extinct throughout its range. The great beauty of the tree, with masses of sky-blue flowers during the dry days of early spring, followed by masses of orange seed-pods in the fall—and a beautifully mottled “ camouflage” patterned bark at all times–has certainly been the main point that has kept it in public awareness. Other valuable and now rare native hardwoods, such as satinwood and mastic, are not now well-known. We can see the distinctive cross-hatched grain of lignum vitae timbers in historic buildings ranging from the lofty Susanaberg windmill to the numerous small homestead sites of the far East End.

Lignum vitae wood is among the hardest and heaviest of all commercial woods, with a specific gravity of 1.3. Specific gravity is a measurement based on the density of water, with 1.0 being the same density as water… so, any wood over 1.0 will sink, as lignum vitae will, readily. (A surprisingly large number of other native woods do the same). What makes lignum vitae wood so valuable is not the density alone, but the combination with the oily resin that permeates the wood, lubricating and making it almost indestructible. “The self—lubricating resinous wood is so valuable that it is sold by weight…It is famed for its special use in bearings and bushing blocks for the propeller shafts of steamships. It serves also for pulley sheaves, deadeyes, and as a replacement for metal bearings in roller mills. Other uses include bandsaw guides, awning rollers, furniture casters, mallets, bowling balls and turned novelties. ” (Little and Wadsworth, Common Trees of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.)

So… back to those names. There is still debate about the origin of syphilis, a disease known as the “great mimic”- Was it originally European or American? Was it present in Europe in a different form before Columbus’s crew came back from the West Indies? Did that crew infect the un-resistant Tainos of this region, causing the disease to mutate, and hastening the Taino’s tragic end? What is sure is that a new form of Syphillis appeared in Europe at the end of the 15th century, spreading rapidly along the trade routes of the continent. At almost the same time, Spanish sailors in the Caribbean were apparently given guaiacum wood by helpful Tainos, and shown how to prepare it as a remedy for the “bubbles” affecting their skin.

The widely accepted date for the introduction of the wood to Europe is 1508. It quickly became the treatment of choice for syphilis —“pox” of course was the plural of pock, as in pockwood (and pockmark), and syphilis was already known as the French disease, hence the frenchwood. The anti-syphilitic properties of lignum vitae were heavily promoted by the Italian physician Francisco Delicado, who credited it with curing his 23- year case of the disease (it was probably spontaneous remission), and published a treatise in the 1520’s entitled Del Modo del Adoperare e Legno de India Occidentale, Salutefero Rimedio a Ogni Piaga et Mal Incurabile (On How to Employ the Wood From the West Indies, a Beneficial Remedy for any Ulcer and Incurable Disease).

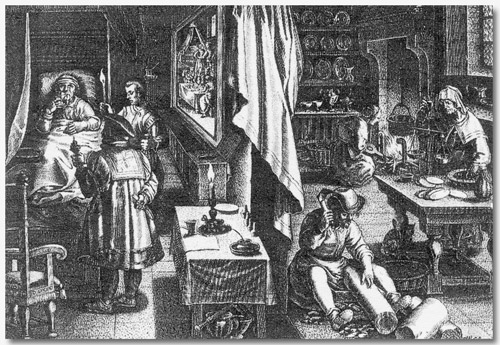

The process of treatment with lignum vitae appears to have been a true case of the cure being possibly worse than the disease. Before the treatment began, it was necessary to purge the patient thoroughly, he was then put on an extreme restricted diet and kept in a dark hot room for 40 days, drinking decoctions of lignum vitae wood three times a day, but allowed no light, fresh air, meat or wine. Sweating, starving, and frequent lignum vitae tea enemas should help effect the cure.

Although it is probable that most of the cures attributed to this harsh regime were temporary remissions due to the length of the treatment, lignum vitae soon became very popular as a cure for a wide variety of other ailments, from sciatica to epilepsy. When it was discovered that it was not actually poisonous when mixed with wine, as had been earlier supposed, a decoction in wine became the favored form of administration.

The use of guaiacum for syphillis waned over the next century, gradually replaced by mercury as the drug of choice. Despite the imaginably dire side effects, mercury remained common in syphilis treatment until the 20th century, while lignum vitae gradually sank into obscurity in the pharmacopoeia, although still employed in combination with other woods and roots as late as 1855.

The Italian scholar Rodolfo Taiani, in Pharmacy through the Ages, considers that one of the main factors in lignum vitae’s popularity was the “…Brilliant sales campaign, prompted by the Fuggers, a powerful German family of traders, entrepreneurs and bankers, financers of the Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) and of princes and prelates. This family had the monopoly of this drug, which became extremely valuable and was sold at very high prices.”

Carstens, writing of St. Thomas in the 1740’s, says “ …There are many different rich families that live well under the Danish flag as the result of their trade, especially in sugar and cotton planting, but also from tobacco, coffee, and cacao…rice, ox-hides and various dye-woods, including ebony wood or bock-wood.” (The black lignum vitae heartwood was often confused with the East Indian ebony.)

Riement Haagensen, describing St. Croix in the same period, said: “One finds on St. Croix two other kinds of trees, fustick (the source of khaki dye, either extinct on St. John or never here) and pockwood, which has brought many a man some thousands and thousands of rixdalers….In the forest, such trees are considered practically as good as money in the bank.”

A few years later, in 1767, the wonderfully thorough recorder of all he found in these islands, the Moravian missionary C.G.A. Oldendorp, goes on at length: “ Pockwood is indeed difficult to work with, both on account of its hardness and its crooked growth. However, it takes precedence over all other varieties of building timber in terms of its sturdiness and durability… Iron will rust away before timbers of this wood begin to rot. The trunk of this tree grows to a width of three to five feet in diameter. (!!!) The wood of this tree is as expensive as fustick, and is, like the latter, exported to Europe in considerable quantities.”

With such fortunes being made, it is a wonder that any native lignum vitae survives on St. John, but it is further testimony to how wild the island remained in the colonial period, compared to many others in the region. Oldendorp’s reference to three to five foot diameter trees should give us pause, though. At Caneel Bay’s main ruins, you can see a large number of small lignum vitaes, grown from seed planted over 50 years ago by the irrepressible Ivan Jadan. Even under Caneel’s luxurious conditions, they’ve got quite a few centuries to go before they’re full grown.

Lignum vitae is one of very few woody plants protected under CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species…almost all other plants with those protections are orchids, cacti and succulents that are still collected from their natural habitats in vast quantities for the illegal horticultural market.

See the related items:

[Buck Island][Natural history]

| Resource | Title | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Article | Bay Rum: A Niche of Distinction in VI History | Schulterbrandt, L.D.N., Gail |

| Article | Forest Island | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Soldier Crab Saga | Boulon, Rafe |

| Article | Nineteenth Century Ornithologist at Estate Adrian | Ober, Frederick |

| Article | Report of the Earthquake of 1867 | Housel, Louis van |

| Article | November Rain | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Of Waterfalls and Rock Carvings | deBooy, Theodoor and Faris, John T. |

| Article | Earth Day 2008 on the SJHS Provisions Grounds | Schoonover, Bruce & Swank, Robin |

| Article | Hike to Estate Retreat | Swank, Robin |

| Article | Earthquakes & Tsunamis: Prospects for the Virgin Islands | Watlington, Roy and Lincoln, Shirley |

| Article | Lignum vitae: Beauty, Strength, and the Fallibility of Medicine | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Fever | Gibney, Eleanor |

| Article | Potluck & Storytelling at the SJHS January 13, 2009 Membership Meeting | Swank, Robin |

| Article | Historical Society Installs Plant Signs at Annaberg | Schoonover, Bruce |

| Buck Island |