Reminiscence of the West India Islands, Second Series No V; Tortola: The Native Missionary

(Edited by Daniel P Kidder, Published by Lane & Scott for the Sunday School Union of the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1852.)

CHAPTER VI

The Methodist Society, in Tortola, was at this time in a very flourishing condition. Large accessions had been made to it during the preceding year. The lady of the governor-general of Tortola and the Virgin Islands was a member; and the governor himself, the Honorable George R. Porter, was very friendly, attending regularly, when his health would admit, and rendering every facility in his power to the missionaries to prosecute their labors. He was a man, too, who feared God, and led a strictly moral life, though he made no open profession of religion until his last and fatal illness.There was, at this time, connected with the Methodists in Tortola, a very remarkable colored woman, named Fanny Waters, who was one of the excellent of the earth. She had been a class-leader for many years, as among the Wesleyans female leaders always are appointed to female classes. Such was the estimation in which Fanny was held, that a large majority of the female converts would select her class in preference to others, to which they would join themselves. The consequence was that her class became too large, and had to be divided. This continued until Fanny led two or three classes, and still new converts would flock to those classes; and when they became again too large, the missionaries would be constrained to divide them, and appoint new leaders to these new classes thus formed.

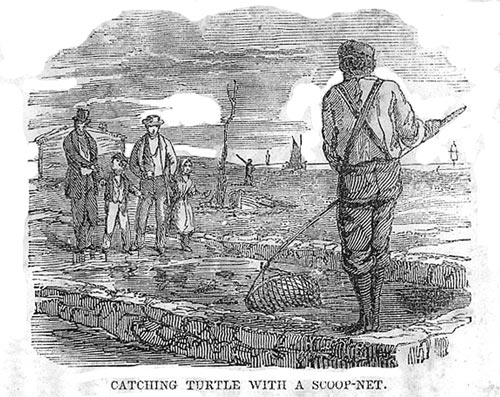

Fanny was indeed a mother in Israel! Her deep piety, unobtrusive and modest deportment, added to her intelligence, made her a general favorite. Everybody, rich and poor, high and low, white and colored, esteemed Fanny Waters; and the very wicked portions of the community had to acknowledge that her life was irreproachable, and that she adorned the gospel of God her Saviour.Mrs. Porter, the governor’s lady, was a member of Fanny’s Sunday class; and it was a matter of pleasing record to Seaton when he aided in the quarterly visitations of the classes, for the issuing of love-feast tickets, to enjoy the privilege of meeting that Christian lady of high rank in the same class with colored females and blacks, some of whom were free, and some yet in bondage.A most remarkable evidence of the high estimation set on Fanny by almost every person who knew her will appear in the following incident. Fanny Waters had been a slave–a slave from her birth. Her mistress was a poor widow woman, who could not afford to emancipate her. As Fanny grew into notice, and became so useful a member in the Methodist Society, and a class-leader, the question became agitated, –ought she to continue in bondage? Some two or three gentlemen, who were merchants in Road Town, took the thing in hand, ascertained what sum her mistress would take for her, and then started a subscription, in order to raise the amount. It was soon done. Planters, merchants, every one having anything to bestow on a benevolent enterprise, regarded it as a privilege to give in this case. The sum was made up; and the year preceding the appointment of Messrs. Whitehouse, Burton, and Seaton to Tortola, Fanny Waters had been made a free woman, through the generosity of those lovers of our holy religion. Often has Fanny adverted to these facts, in conversation with the writer of this little book, while the tears of gratitude to God and his people rolled down her cheeks.As soon as the missionaries were a little settled, their kind friend, Mr. Moore, of St. Johns, insisted on a visit. Mr. and Mrs. Whitehouse could not join the party, but the Burtons and the Seaton family, in Moore’s fine large boat, were soon rowed over, and spent a pleasant day at Mr. Moore’s beautiful country seat. This spot was most romantically located. Like the mission premises at West End of Tortola, it was also situated on a narrow part of the island of St. Johns, with this exception, that the buildings were not on the most elevated part of the premises, but on the brow of the hill facing the south. A good path led from the beach, on the north or Tortola side, up the hill, and then down on the other side, to the residence of the family. The buildings were comparatively new; the old house in which Mrs. Bryan had resided having been destroyed in the hurricane of 1819.To the south side, one of the most beautiful little coves that the strangers had ever seen lay at the foot of the hill. It was so completely shut in from the wind, as to be almost always calm and smooth, through the water would be gently lifted up and down by the rising and falling of the tide. Here Moore had constructed an ingenious turtle-kraal, which afforded him, at all times, a plentiful supply of that delicious kind of shell-fish.The West Indians are very fond of turtle. The waters of the Caribbean Sea, the coves and bays around their islands, abound in the green-back as well as the hawk’s-bill species. The former is preferred, both for the delicacy of its meat, as well as the superiority of its shell.Mr. Moore’s pen, or kraal, as it is there called, was built in the following manner. A wall was made on the beach, running out into the water, describing three sides of a rectangle, the beach itself being the other side, with a wooden gate. This wall was high enough to be above the high-water mark; and loop-holes were left, in its construction, to admit the constant ingress and egress of the water.Mr. Moore owned slaves, and one or two of his men were very expert at catching turtle, by means of a net adapted to the purpose. The turtle, when caught in the net, were put in this pen or kraal, and then fed with the entrails of poultry, and other kinds of flesh or fish, and some kinds of vegetable matter, such as a variety of the cactus, the prickly-pear, so common in these islands. In these pens turtle grow fast, and become very fat; and at any time Mr. Moore would have a very fine dinner, by causing one of his men to stand on the wall, and, with a kind of scoop-net attached to a pole, with a hook at its end, catch any one selected from the rest, as they come up to gather around the food thrown in for them.The day was most pleasantly spent by these Christian friends. A Mr. Richardson, a native of St. Croix, with an amiable wife and family, who lived near Mr. Moore’s added not a little to the social intercourse. He, too, had been the subject of God’s saving grace, and was now a member of the Methodist Society, and one of Moore’s class. Mr. Seaton had known him in St. Croix, when both were out of the ark of safety, and it was a source of mutual pleasure to them to talk over the great things which God had done for them.

CHAPTER VII

As the gentlemen were walking around the premises, enjoying the scenery, and engaging in conversation, Mr. Moore remarked to Seaton, “Have you heard that our friend Richardson here came very near losing, at least, a thousand dollars lately?”“No, I did not. By what means was it?”“Why, two of Mr. Coakley’s valuable slaves stole his boat, and were making their way rapidly to Tortola; but, most fortunately, Richardson heard of it in time to pursue them, and just overtook and captured them before they landed.”“Why, cannot a fugitive slave be arrested in Tortola?”“No. So soon as they arrive on British territory, and report themselves to the authorities, they claim the protection of British subjects; and a man of our community, or any other Danish island, may as well give them up at once as attempt to recover them. Do you not think it hard in the British government to hold slaves themselves, and yet make free the slaves of other nations?”“To look at the subject in that light, it would seem so. But I suppose this is the true idea. They have long ago abolished the African slave trade; and their armed vessels capture slaves, bring these slaves to British ports, and set them free. No individual, then, of any nation or complexion, coming into a place where the English flag flies, can be regarded as a slave.”“But why not, then, set all their own slaves free?”“No doubt that will be done before many years have elapsed,” answered Mr. Burton. “Things are looking that way very much in England. Wilberforce is at work, and that with certain effect.”“Still, I think,” said Mr. Richardson, “that they should give up our people who abscond from us, and go to their islands, if we can prove our property.”“Do many of them run away from St. Johns,” asked Seaton.“Instances occur very often. Hence the law about boats. Every man having a boat is subject to a heavy penalty, if that boat is not every night hauled up above high-water mark, chained to a strong post well planted in the ground, and secured by a good lock and key. In addition to which, the boat must be scuttled, and the scuttle carried away, and locked up by the owner.”“How did they come to get your boat, if you took all this precaution?”“Why, I must confess that it was through absolute carelessness on my part. I will tell you how it was. I had been at Tortola all day, on business. I had many little purchases to make; for it is so much nearer than St. Thomas, that many of us Danish subjects prefer to trade with the English merchants in Road Town. We were very late on our return home. We had a very heavy row, for the wind and tide were against us, until we came round the point, nearly opposite your West End establishment. On arriving at my landing-place, I said to the boys, ‘Never mind locking the boat; scuttle her, and carry home the scuttle: that will do. It is so late that nobody perceives us, and we can send down early in the morning, and chain and lock her fast to the post.’ But, behold, in the morning the first news I learned was that the boat was gone!”“Why how in the world could the fellows make any head-way in a boat with the scuttle out? I wonder she had not filled the moment they launched her!“O, they took care of that! They had no means of making a regular square scuttle of wood, to fit tightly in the place left open for it, but made a kind of wad, or stopper, of old cloth, dried plantain flagging, and other materials, and so plugged up the hole. But it was so imperfectly done, and they in such a hurry, that the boat leaked very much. There were but two of them. I know the fellows very well; and I suppose, as one had to bail out the boat almost continually; and the other, with one oar, and that a very poor one, for my boys brought up our oars, could make very little progress in his voyage; and, owing to this, I was enabled to overtake them”“Did they make any resistance at all?”“None whatever. Harry, the principal fellow, as soon as I drew near to them, and ordered them to stop and surrender, cried out, “Ah, Massa Willliam, you caught me! But a little longer, and I would have been out of the clutches of old Coakley, I tell you. I’ll go back. You shan’t have any trouble with me; but I’ll not be so easily taken next time, I assure you.”“What did Mr. Coakley say?”“The old gentleman was very much excited, and censured me a good deal for neglecting to secure the boat. But we are relations, and of course he would not complain of me to the authorities. If the men had made good their landing on English soil, however, I should have been compelled to pay Mr. Coakley for them, at an appraisement made by three gentlemen–one chosen by him, another by myself, and the third by those two. These would have fixed the price of the slaves; and I should have also been fined, for not securing the boat, and, what is very likely, have lost my boat also; for they are very apt, when they abscond in such a manner, to send the boat adrift, and the tide carries her out to sea.”“Has brother Moore, or yourself, ever lost any of your people in this way?” inquired Mr. Burton.“Not one,” answered Moore. “I can trust my men to go in my boat to Tortola, any day in the year. They land, walk about, go where they please, and I have only to say what hour I want them to be ready to start, and when I go to the boat, there they are, punctually and faithfully.”“It is the same with my people,” said Richardson. “I know they would not leave me; for they have had numerous opportunities of doing so.”“Well, now, to what do you ascribe this faithfulness?” inquired the missionaries, almost simultaneously.“To the influence of our holy religion,” said Moore. “Some of our people are Christians, and would not leave us, because they think it would be wrong. Again, they are treated kindly by us. We do this for conscience’ sake. All their wants are supplied; and they do no kind of work, nor any amount of work, but what they can reasonably perform. In this condition, they doubt whether they would be benefited by running away from us; and then without friends, money, or home, being thrown on their own resources.”