Bay Rum: A Niche of Distinction in VI History

Bay rum is tightly woven into the fabric of Native Virgin Islands culture. In the olden days, every single pantry in the Virgin Islands contained a bottle of bay rum. It is the one historic industry that St. John and St. Thomas can claim as being our very own.

In Virgin Islands history, St. Croix, due to its achievements in agriculture, became known as the garden of the West Indies – where sugar was king. St. John, however, the smallest of the three Danish West Indian islands, was noted as the home of the bay tree from the leaves of which was produced the famous bay rum of these islands. Virgin Islands bay rum attained the reputation of being the finest in the world.

The prolific cultivation of the bay tree on St. John supplied great quantities of leaves. It is from the leaves that the essential oil of bay was extracted which provided St. John with its most important industry. St. Johnian bay oil was shipped to its sister islands of St. Thomas where it was manufactured into bay rum. Possessing one of the finest deep-water harbors in the entire Antillean chain, St.Thomas was a center of commerce and a natural conduit for exporting the finished product to many parts of the globe: Europe, South America, the United States and the Caribbean.

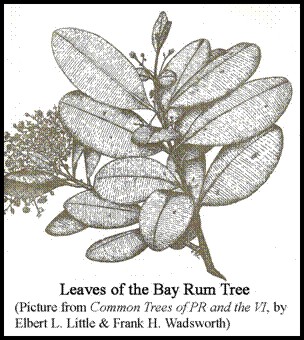

Quite often, bay rum is confused with the distilled alcoholic beverage that is known as rum. They are two different things. Scientific nomenclature has identified the bay tree as Pimenta racemosa (in the myrtle family.) The drink referred to as distilled rum sprits is made from sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum.)

The common (everyday) terminology for this plant is “bay”, however, as time passed, one of its names was given to the tree and the two terms were used interchangeably: bay rum.

The estate owners on St. John paid the leaf pickers eight cents per bag for their labor-intensive work; each bag could hold up to 75 pounds or more but contained no less than 60 pounds apiece. The lower the weight, the lower the wage. The leaves were then carried to a still apparatus where the oil was extracted.

Some authorities recommended three pickings of the leaves per year. Others believed that it was best not to interfere with the trees for a whole year; in this way, the leaves would increase in oil content the longer they remained on the tree.

Leaves can be plucked from a tree as young as three years old without inflicting any injury to it. Pickings during the first few years will yield about 25 pounds of leaves per year. When the tree has reached its maturity at least one hundred pounds of leaves can be counted annually, providing there are favorable weather conditions. At about ten years of age a bay tree reaches maturity and will continue to bear leaves for 50, 60 and 70 years under ordinary circumstances.

Experienced growers had differing opinions on how to create conditions that produce a superior-quality leaf and the best yield while considering the welfare of the tree. It was felt that for the benefit of the oncoming crop, breaking the branches by hand was better than using pruning knives.

There are two methods for making bay rum. One way is to mix the bay oil with rum or with alcohol and water and then distill it. Another way is to distill the leaves directly into the alcohol instead of first extracting the bay oil. From the latter method, the product obtained is considered to be superior in aroma and strength. From one quart of the oil a lot of bay rum can be made, depending on the strength to which it is distilled.

In the early 1900s, prior to the transfer of St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix from Denmark to the United States, approximately 4000 quarts of bay oil were produced in St. John on an annual basis. About 60,000 cases of bay rum (each case contained twelve quart-size bottles) were produced on St. Thomas. Large amounts were sent to Panama through the canal from whence it was transshipped to countries on the western coast of South America. The Virgin Island families who were the principal operators of bay-leaf enterprises on St. John were: E. W. Marsh, A. White, G. Bornn and A. Lindquist. The leading St. Thomas manufacturers of bay rum on St. Thomas were H. Michelsen, A. Riise, the St. Thomas Bay Rum Co., A. Vance and Valdemar Muller.

After the Transfer, the Van Beverhoudt family of St. Thomas produced and sold very fine bay rum and soap products. In these modem times, the Virgin Islands custom of making high-quality bay rum is being kept alive by the West Indies Bay Company, headquartered in Havensight on St. Thomas. Mr. Jerry Woodhouse, who owns the business, explained that his operation dates back here to 1946. They produce pleasant- smelling fragrances for ladies and men that are attractively packaged in bottles that have a natural looking island-type straw appearance.

Native Virgin Islanders were very knowledgeable on how to put the various parts of plants to good use. In Virgin Islands culture, the bay tree was used for five different purposes:

- AROMATIC – Any unpleasant odors present in a dwelling were eliminated by hanging the aromatic branches of the bay rum tree on the interior walls of the building or by laying them down on the floor.

- COSMETICS – the oil of bay essence was used in the manufacture of fragrant perfumes, soaps and colognes.

- MEDICINAL, FEBRIFUGE – If a person was ill with fevers, chills, aches and pain, the bay rum liquid was applied externally as an emollient to the patient’s body in the form of a sponge bath. Native Virgin Islanders would describe this usage as having a “cooling” effect on the body’s high temperature.

- INSECT REPELLENT – When the leaves of the bay tree were burned, the smoke that was given off was used to drive away the mosquitoes.

- DIETARY, TRADITIONAL CUISINE – Bay leaves are used as condiments due to their contribution of spicy flavoring to the delicious Creole cooking of the Virgin Islands, specifically in the preparation of stews, sauces and soups. (Editor’s note: the bay leaf typically used in North American and European cookery is a member of the Laurel family Laurus nobilis.)

There is a majestic bay tree in the beautiful gardens of the Villa Notman Historic Virgin Islands Home Museum on Black Beard’s Hill. The next time you are in the neighborhood, stop by and notice the exquisite multi-brown shades of its unusual bark.

Native Virgin Islander Gail Shulterbrandt, L.D.N., is director of the Haagensen House Museum, a writer and historian, a member of St. Thomas Friends of Denmark Society and Blackbeard’s Corporation, co-editor of the St. Thomas Historical Trust’s Welcoming Arms publication, retired State Director of the USDA Nutrition Programs, Virgin Islands Government and Licensed Dietitian, and nutrition consultant in private practice. This article was excerpted from an article originally appearing in the St. Thomas Trust’s Welcoming Arms, by permission of author.

[Bay rum][Economic activity][Natural history]