Lameshure Bay Explore

Yawzi Point’s Great Lameshure Estate House

Its rounded entry steps

overlook the cotton magazine

(By David Knight, summarized by Robin Swank)

On Saturday, March 17th, a record 78 hikers met at VIERS to join SJHS President David Knight for a tour of the physical remains of three contiguous estates (Great Lamesure, Little Lamesure, and Bowe) which were consolidated in the latter half of the 18th century to form a single Lamesure Bay estate. David shared the available historical record of these plantations and invited us to conjecture upon what is not yet fully documented.

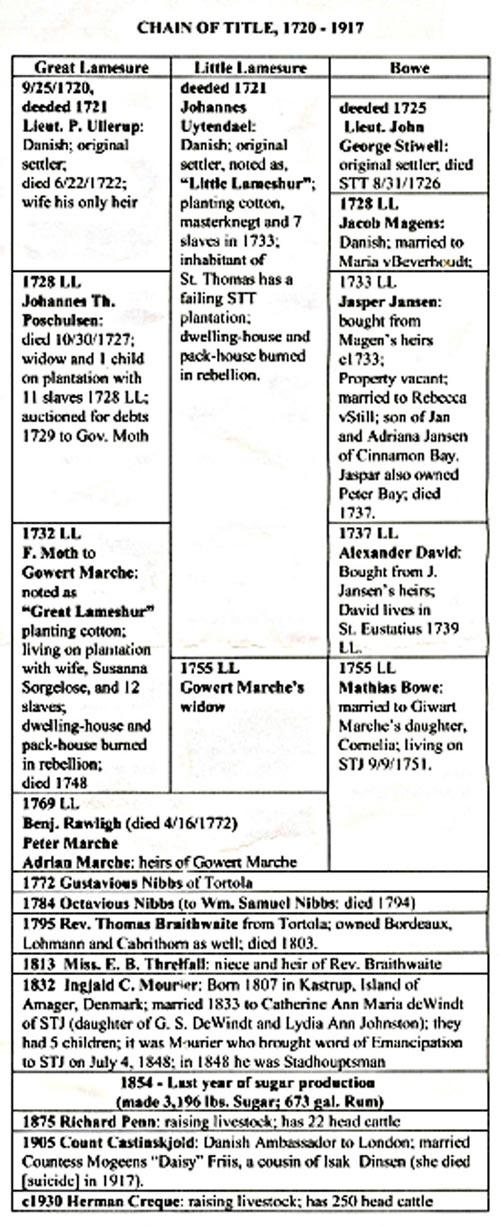

“Lamesure and Leinster Estates share something in addition to beginning with L; these estates both have obscure early histories.,” our historian began, as he passed out the Chain of Title (See next page) for Lamesure. “There is still much work to be done on Lamesure (or Lameshure, or Lameshur, or LaMesure)’s early history; there exists a good deal of oral interpretation and some educated conjecture that needs to be followed up with scholarship.”

Lieutenant Ullerup’s plantation situated on Great Lamesure Bay is the oldest of the three Lamesure estates; it was deeded to him in 1720. Situated on a dry windy ridgeline on what is today called Yawzi Point, the estate house foundation with at least two gravesites on the west side of the house overlooks the ruins of what appears to have been a cotton magazine (warehouse), necessary to keep the fragile harvested cotton dry. Farther inland are remnants of the slaves’ compound. Because the grounds were cleared last year by the Sierra Club, the outlines of the estate’s primary structures depicted on Peter Oxholm’s 1780 St John map can be clearly distinguished in the bush. Stories that this site was once used as a quarantine station remain speculative, and David urged anyone with solid references to support this claim to share that information with us.

A neighboring plantation on Little Lamesure Bay was deeded to Johannes Uytendael in 1721. This appears to have been a more developed property, having an overseer and seven enslaved laborers on site by 1733.

The third plantation at Lamesure, the Bowe Estate, was deeded to Lt. John Stiwell in 1725. Unlike the other two estate complexes, the house does not appear on the 1780 Oxholm map, and history documents it as mostly unoccupied. Nor is there evidence of the Stiwell house today. David speculated that it may have been the small site that fell to the bulldozer when the modern road over the hill to Lamesure from the east was built some years ago. We may never know, however, for all that remains of that site today is a suspicious bunch of aloe and other usually domestic plantings on both sides of the road.

Early histories of these sites share the common themes of cotton cropping (probably accompanied by grazing and the self-sufficiency requirements of liming and provisioning), transitions of the land from one owner to another due to early death, sales at auction because of debt, and damages during the 1733 slave rebellion, which began at the Coral Bay end of St John.

Cotton was the primary crop on the dry south side of St. John in this early period. It is believed cotton was already planted on St. John, possibly initially by Indian textile weavers, by the time the first permanent Danish–sanctioned colonists arrived. It was sea isle cotton, noted for its oiliness and valuable for sail making. It could be sold either as stone cotton (with the seeds), or ginned (free of seeds). As a crop, cotton harvesting required only a modest degree of wealth for the purchase of slaves designated not strong enough for sugar work (i.e. macrons). Macrons could also comb or gin the cotton, yielding the seed for future plantings.

Another valued commodity of the time was quicklime, which was not available in mineral form here, but made by burning dried coral heads. In one historical inventory of the Lamesure estate, bags of lime are among the most highly assessed product on the property. Was Lamesure named for the chalk-white cliffs (lime shore) these settlers hoped were made of lime? Or was it named for the ‘limes ashore’ planted by earlier seamen? Eleanor Gibney pointed out probably not the latter, as citrus would have been called ‘lemons’ in that era. So, how about Lemon-shore?

There was much conjecture about the function

of this building at Little Lameshure; the early

candidates were lime juice still or lime kiln.

According to a survey conducted by James

McGuire published in 1923, there were both

a bay rum still and a limejuice still on the

Lamesure estate. There is also a separate ruins

of a rum still associated with the sugar works

on the site.

Consolidation of the Lamesure properties occurred c1755, when Gowert Marche (the owner of Great Lamesure since c1732) purchased the neighboring Little Lamesure and his son-in-law Mathias Bowe purchased the former Stiwel parcel. But by 1769 the holdings began to fragment to multiple Marche heirs. It was not until 1776 that all 3 properties came under the undivided ownership of Gustavious Nibbs of Tortola.

The Nibbs family appears to have found no success with the Lamesure estate. After a devastating hurricane laid waste to the property in 1793, all of the Great and Little Lamesure properties were sold at auction to the owner of the adjacent Bordeaux estate, the Reverend Thomas Braithwaite, who was building and consolidating his holdings in the Danish West Indies. David pointed out that many of the wealthier British planters, like Braithwaite, A.C. Hill and Alexander Fraser, who had mixed-race children, purchased holdings in the more ‘liberal’ Danish West Indies to establish their ‘free-coloured’ children. British law in this era forbade them from passing on ‘homeland’ properties to non-white heirs. It is estimated that at Emancipation nearly 40% of St John estate owners were members of the island’s rapidly growing ‘free-coloured’ population.

Upon Reverend Braithwaite’s death, his free-coloured mistress inherited Bordeaux and their daughters inherited the Lohman estate in Coral Bay, while his in absentia white British heir, Elizabeth Threlfall, got the Lamesure property. It appears that Miss Threlfall never set foot on St. John and that the estate lay fallow during her ownership.

In 1832 Ingjald C. Mourier, a Danish citizen, purchased Estate Lamesure and immediately set out to develop it into an active sugar cane plantation. It appears to have been Mourier who built most of the industrial structure now visible along Lamesure Bay and the estate house atop the hill. This house is the longest continually occupied estate house on St. John. It is currently owned by the Park (and occupied by a very gracious Park Ranger, who invited all of us to tour the inside.) According to estate inventories, Mourier’s new masonry and tile roofed dwelling had an attached and fireproofed cookhouse (the latest thing!), and a fire engine (a pump on a cart), just in case.

Mourier’s estate growth can be tracked through tax records and a series of ‘appraisements,’ probably required because he had outstanding loans. The Estate’s enslaved population of 22 tripled at the height of his ownership; he created the water source needed for sugar production by digging out a pond near the bay and quickliming it to create a leakproof reservoir. His property was valued in 1843 at 27,274 Spanish pieces of eight, the preferred currency of the time because its assayed intrinsic value was true, unlike that of the Danish rigsdaller, which was made of inferior ‘German silver’ or silver-plate over a copper core. You have to wonder in this period of sharp economic decline if Mourier’s ability to pay the taxes on his increasingly valuable property kept pace with the profits he could generate from sugar and raising sheep! By 1847, the year before emancipation, of the 235 acres on the Estate, only 24 were planted in sugar cane. After Mourier’s tenancy, Lamesure Estate was purchased by Richard Penn, a cattle breeder who acquired all the southern lands between Salt Pond and Lamesure. In 1905 he sold it to the Count and Countess Castinskjold.

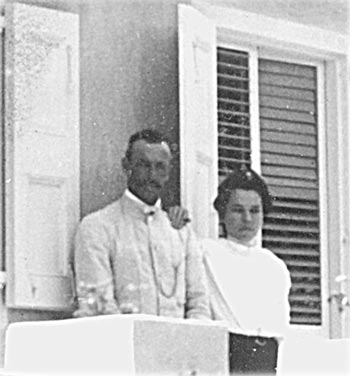

Count and Countess Castinskjold

1905 shows the first donkey (‘ass’) in inventory! According to a description read by Chuck Pishko, the Countess Mogeens ‘Daisy’ Friis Castinskjold was ‘an elegant and wild girl,’ who would ‘thrill at the possibility of total ruin.’ Quite possibly she married her totally acceptable Danish Ambassador as a family accommodation. Remarking on the picture at right, one knowledgeable SJHS member among the hiking group said—‘That was more clothes than she was ever known to wear.’

This hike goes to prove that the SJHS are a hardy bunch! We covered a lot of educational territory as well as a lot of physical ground. We owe a huge thank you to Randy Brown, the VIERS team, and Clean Island International Co. for providing our midday food and drink, and for hosting us at VIERS, providing us with an additional educational experience.

WHAT’s IN A NAME? Do you know how Yawzi Point got its name? A 1794 Lamesure Estate inventory lists a ‘sickhouse’ on the estate. Was this structure on Yawzi Point? Is the name Yawzi Point derived from the disease yaws? Or is it derived from some other source? There are many open questions on this topic.

Yaws is a disease thought to be of Caribbean origin; it is a chronic infectious disease which first exhibits symptoms of open sores, caused by a spirochete that enters through cuts or scrapes; it then attacks the bones and joints. Today one injection of penicillin cures it. Most at risk are children under 15. The derivation of the word is obscure; the Carib word ‘yaya’ is the word for ‘sore’; alternatively the African word ‘yaw’ may have meant ‘berry’. Yaws is also, therefore, called frambesia tropica. (Summarized from www.MedicineNet.com)

In the early days of Lamesure diseases like yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera would have been common, and the isolation of Yawzi Point at or near an abandoned estate house might have been an ideal quarantine station. Perhaps young children with yaws were also housed there.

Can you confirm when the name Yawzi Point was first used and why?? Enjoy a free SJHS T-shirt if you can!

See the related items:

[Bay rum][Great Lamesure][Little Lamesure]

| Resource | Title | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Article | Bay Rum: A Niche of Distinction in VI History | Schulterbrandt, L.D.N., Gail |

| Article | Post-Plantation and Pre-Tourism: Life and Work on St. John in the Early 20th Century | Fortwangler, Crystal |

| Article | Lameshure Bay Explore | Knight, David |

| Article | Huguenot at Lameshur: Captain Ingiald Mourier | Smothergill, Dan |

| Article | Lameshure Bay Estate of the 1950s | Schoonover, Bruce |

| Article | A Remembrance of St. John | Knight, Anna |

|

Bay Rum Factory in Coral Bay, 1919 Creator: Tyge Hvass Owner: Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark Photograph |

|

|

In the cotton field at “Lamesure” St. Jan, Danish W. I. Creator: J. Lightbourn Owner: Private collection Colorized Post Card |

|

| Estate Great Lamesure | Qtr=Reef Bay. Owner=Braithwaite, Thomas. Crop=Cotton. | |

| Estate Little Lamesure | Qtr=Reef Bay. Owner=Braithwaite, Thomas. Crop=Cotton. |