Quicklime – An Essential Material of the Colonial Period

(Editor’s Note: On March 25th, Society President, David Knight and Mr. Reggie Callwood will help us explore the ruins at Cinnamon Bay and review restoration work and techniques used by Mr. Callwood in the 1960s and 70s to stabilize and preserve historic sites throughout the National Park on St. John. As background, David has excerpted and expanded upon some passages from his book, Into The Light – The Enigmatic History of Water Island in the Danish West Indies 1672-1917, which deal with the use of quicklime for both mortar and plaster.)

Five materials were the basic elements of sound construction during the early Danish colonial period in the West Indies: brick, stone, sand, timber, and limestone, from which “quicklime” for mortar and plaster was produced. Of these, only brick was initially imported, arriving in great quantities in the holds of incoming Northern European ships, as ballast. While its consistency of form and geometric configuration made brick a perfect medium for leveling courses and precise detailing in corners or around windows and doorways, it was expensive when compared with other materials that could be harvested locally. For this reason, bricks were used sparingly in anything except high-end construction.

Among the resources the islands of the West Indies possessed in great abundance were stone and sand, and it was some time before the readily available sources of these commodities became depleted to the point where it became necessary to travel any great distance to acquire them. Timber and limestone, on the other hand, were quickly depleted.

While the northern Virgin Islands are not known to have possessed any great quantities of geologically formed limestone, it had long been known that sedimentary, coral-based sand stone, coral, storm-strewn coral debris, shells, and even some beach sands, which the islands did indeed possess in abundance, could be utilized in the same manner as true limestone to produce quicklime. It can therefore be stated with certainty that the Danish term “kalkstien” (limestone), when used in the context of the Danish West Indies colony throughout the eighteenth century, refers not to a specific substance but to a mélange of locally available high-calcite materials.

When coral, chalk, or limestone (calcium carbonate) are heated to temperatures of 1652° to 2012° F (900° to 1100° C) carbon dioxide is driven off leaving calcium oxide, a powdery substance, more commonly known as quicklime. Quicklime reacts thermally when brought into contact with water, producing calcium hydroxide. This substance continues to react with the atmosphere and eventually re-solidifies back into calcium carbonate; thereby completing the cycle from a solid mass, into powder, and back into a solid form.

The origins of lime production can be traced back to prehistoric times. Evidence of stone furnaces for lime burning have been unearthed in Khafaje in Mesopotamia dating to as early as 2450 BC, and we know that lime mortar was used in Crete in the Middle Minoan period, about 1800 BC. In Europe and Great Britain, large quantities of lime were utilized in the construction of the great churches, castles, and palaces of the middle ages. Still, it was not until the turn of the seventeenth century, when the use of brick became commonplace in vernacular construction, that the demand for lime mortar and the trade of the limeburner became widespread.

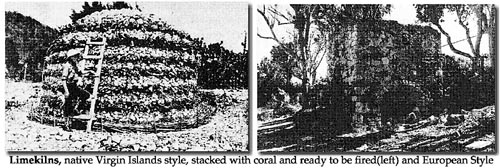

During the establishment of the Danish West Indies in the late seventeenth century, a limekiln would necessarily have been among the first structures to be erected before any substantial development could begin. Brick and stone, set and bonded with lime mortar and then sheathed with a lime-paste plaster, were the primary elements of sound construction throughout the colonial period: utilized first and foremost for the construction of fortifications, and later, as development progressed, for the erection of watch towers, warehouses, processing facilities, and residences.

As a spin-off of the lime business in the West Indies, brain coral also became an important element of local construction. Hoisted from the sea floor into ships, coral was easily sawn or chiseled into shape when freshly harvested, but upon exposure to the atmosphere, it quickly hardened into a highly durable building material with exceptionally high compression strength. For this reason it became a prized and valuable substance, utilized almost exclusively for comer and keystones. Coral culls from the shaping process were used as pointing material to fill and strengthen stone walls, while any leftovers were added to the limekiln for conversion to quicklime.

The importance of quicklime and coral to the islands’ developing infrastructure can not be overstated. Even half-timber buildings and rudimentary wattle and daub structures, which were erected by both enslaved laborers and the colony’s less affluent free citizens, required large quantities of lime-based mortar to construct. Packed lime floors and lime-based whitewash were also common features. Beyond its use as a construction material, quicklime had several important agro-industrial applications. It was applied as fertilizer to cane fields, used as a clarifier in sugar and indigo production, and as a drying agent in the tanning process. In short, quicklime was far more than a simple commodity. It was an ongoing necessity of colonial life.

[Economic activity][Quicklime]