The St. John Market Basket

For as long as I’ve been involved with the St. John Historical Society–and probably ever since the Society’s inception in the mid-1970s–we’ve wanted to have a logo: an image that evoked St. John’s history and culture and some of the unique attributes of both.

The St. John market basket — a basket unique to St. John which seems to hold the spirit

of St. John in its grace and practicality, and the fruiting branch of the seagrape — a plant

that has sheltered St. John’s shorelines for millennia, has been adopted as the logo of the

St. John Historical Society.

(Image courtesy of Society member Kimberly Boulon)

In recent years we had considered and rejected a range of ideas, and the one we kept coming back to was the St. John market basket. I don’t think we could have chosen any more appropriate a symbol. Made from indigenous materials, strong and durable, beautiful and evocative—a commonplace object that seems to hold the spirit of St. John history in its grace and practicality. To enhance the logo picture, we chose a fruiting branch of seagrape (Coccoloba uvifera), a plant that has sheltered St. John shorelines for millennia. Thriving from the well-watered beach edges of the north shore to the harshest cactus covered cliffs of the south east coast, seagrape trees provide shade, fruit, and fuel while they hold the edge of the land, preventing seaward erosion.

The origins of West Indian basket making go a long way back. The Amerindian people who settled the islands made baskets from indigenous materials, and perhaps some of their knowledge of those materials was transferred to the earliest people arriving from Europe and Africa. Certainly, over time the basket making styles—and the materials used—developed very differently on different islands. The French community on St. Thomas brought fine palm-leaf weaving traditions from St. Barts. Down island, various grasses such as vetiver and khus-khus are still woven into an array of useful and ornamental items. The few remaining Caribs on Dominica create basketry with the same materials and techniques they’ve used for many centuries.

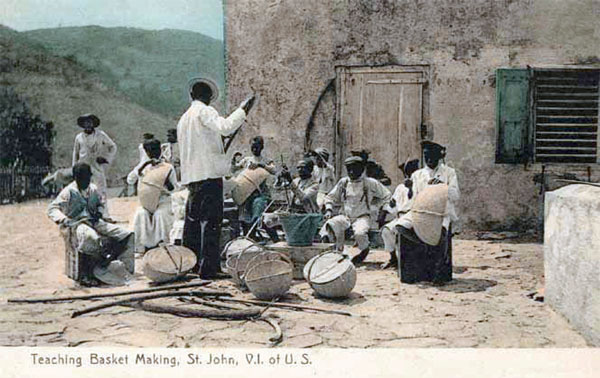

“Teaching Basket Making”

at the Emmaus Mission Station in Coral Bay

by Johannes Lightbourn, c1905

(Image courtesy of David Knight)

Here on St. John there were two primary materials used, both of them indigenous to the island. Large sturdy baskets with strong frames–market baskets, melon baskets, etc., were made from hoop vine (Trichostigma octandrum), and finer, lighter –weight items were woven from basket wist(Serjania polyphylla). Other materials were occasionally used, and some authors have misidentified plants in the past, but these were the common ones.

However West Indian the material, the style of the St. John market basket is essentially European. Baskets of similar type were made throughout Europe, but most notably in Germany, supporting the belief that Moravian missionaries brought the techniques of frame basket making to the West Indies. Although willow would have been the European wood used for similar baskets, the material for large St. John baskets has apparently always been hoop vine, a large, woody, and high-climbing vine in the pokeweed family. While hoop is very common on St. John, the remaining basket-makers were having difficulty finding good hoop by the 1980s. They recognized that some stands of hoop were superior; this may be related—at least in part—to the amount of sun the plant is growing in. With sections of the island cleared for plantations, and later for large cattle ranching operations, there would have been many sunlit edges of forests where the vine would have thrived. Today it tends to climb rapidly to the forest canopy and the relatively slender stems used for basketry are hard to access.

It was very important to gather the hoop at the dark of the moon, which ensured the durability of the stems. The preparing of the vine was tedious and difficult: the basket frame was formed from the entire stem, simply stripped of bark and smoothed, but the thinner woven pieces had to be carefully cut from the lengths of prepared vine with sharp knives. The actual weaving of a full-sized basket took about two days for a master basket maker—far longer for the student!

Whenever the skills of superb basket-making may have developed on St. John, the island’s baskets became an important industry at the beginning of the 20th century. Two of the earliest postcards from St. John show basket-making: one depicts an adult class at the Emmaus Moravian church c 1905, the other a family of basket-makers somewhere in eastern St. John, probably in the same year. Hoop baskets were always made primarily in the Coral Bay Quarter of the island. The East End community specialized in wist work, using the much finer stems of basket wist, Serjanea polyphylla, generally more suited for delicate objects such as placemats, coasters, or sewing baskets, not required to carry much of a load. The hoop basket, on the other hand, was used to carry anything you could fit in it, “from fish to babies,” as Bernie Kemp noted; and they lasted for many years—sometimes for many decades.

Thousands of baskets were exported from St. John in the first half of the 20th century. Many were sold through the Virgin Islands Co-Operative, the venue for marketing native crafts that occupied a large waterfront building in Charlotte Amalie, selling to the numerous passengers of the first pleasure cruises of the 20s and 30s. St. John baskets were also sold as far afield as Macy’s in New York City, and in Europe, and were shown at many exhibitions and fairs internationally. St. Johnians regarded basket-making as a very important source of cash in an economy where money was scarce and people’s needs were largely met through their own labor and trading good and services with others.

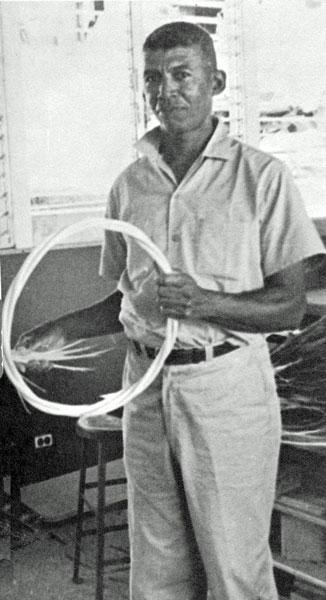

Herman Prince

from Arts in the US Virgin Islands,

VI Council on the Arts, 1967

St. John continued to produce baskets throughout the 20th century. Although it was increasingly hard to make significant income, many of the artisans felt that they had to keep using their skills. When Dr. Bernard Kemp moved to St. John in the late 1980s, his background in the economics of arts and crafts soon led him to two conclusions: the baskets still being made on St. John were of amazingly high quality– and the makers were not charging nearly enough for them. Following Bernie’s advice, the basketmakers priced their wares as works of art rather than utilitarian objects—and, to their astonishment, visitors and the new more affluent residents were happy to pay prices that reflected the time and skill involved in the production.

The most respected basket -maker of the early 20th century was Ernest Sewer. He taught dozens of young St Johnians up until his death in 1939. One of his students, Herman Prince of Estate Zootanvahl, became the best-known basket-maker as the island began a period of rapid change in the mid-20th century. Mr. Prince taught basketry production in the public schools (there were four on the island at that time) for 30 years; after he retired in 1976 he continued to teach a class for adults. Sponsored by the VI National Park, the weekly class at Hawksnest Beach was primarily attended by continental transplants, all of whom took away something much more valuable than a skill—many of their baskets were pretty pitiful, it must be acknowledged—they gained a genuine understanding of the values and social structure of the unique St. John community that was already almost vanished. Mr. Prince was a strict teacher, but not without humor, and inspired love and respect in all who knew him.

With the passing of Mr. Prince and the other active St. John basket makers in recent years, the island has lost a major link with our culture and history. Even with the elevated prices that the best baskets now commanded, sadly, no young St. Johnians were attracted by a vocation that requires so much patience and self discipline.

The St. John basket reflects many of the aspects of St. John that the SJHS is striving to record and preserve. Additionally, the essence of the basket is a container that can hold all the things we need to carry… The island’s history is a very big thing, as big as all the people who have come before us, but if anything can help carry the load, it’s a St John basket.

References:

- Emmaus Moravian Church, Coral Bay, St. John 200th Anniversary Booklet, June, 1982

- Guth, Ann, Baskets of St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands Ann Guth, St. John VI 1982

- Harrison, Dana, Herman Prince, in St. John People, American Paradise Publishing Company , St. John VI 1993.

- Kemp, Bernard A., Basketmaking on the Island of St. John. The Clarion, America’s Folk Art Magazine, Volume 15, No. 3, Summer, 1990

- Lewisohn, Walter and Florence, The Living Arts and Crafts of the West Indies, Virgin Islands Council on the Arts, St. Thomas VI 1973

- Moore, Ruth S. and David M. Hough, Arts in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Caribbean Research Institute of the College of the Virgin Islands, St. Thomas, VI 1967