Estate Misgunst Meander Led by David Knight and Eleanor Gibney

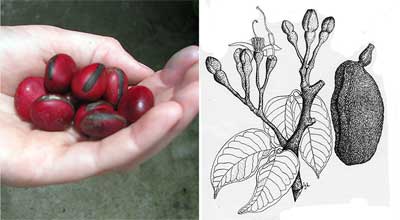

V.I. and on right, a detailed drawing of the Locust tree

(Hymanea courbaril). It is a multi–purpose tree—its pods are

edible, the sap produces a natural medicine, and the wood

makes admirable timber.

There were a succession of inland Estates on St. John–Maria’s Hope, Bordeaux, Mary Simpson, Pasquero/Josie’s Gut and Misgunst. All eventually failed as sugar plantations. On our March 14th hike, David Knight and Eleanor Gibney led us down a naturally reforested trail, in part an old Danish cart-road, to Misgunst. The air is perfumed with bay tree. We find guavaberry and amarat; along with white cedar and casha, amarat was cut for charcoal. There is also a concentration of red locust trees, used not only for timber, but also for its edible pods and resinous sap, or copal, which is used to produce a natural medicine. It was a cool beautiful day for the 30 hikers.

Misgunst was among the first of the inland plantations to fail. Also, it was a property of little value, having no access to fresh water for planting, nor to salt water for shipping. Some inland estates diversified into coffee or cocoa, or were later used as provision grounds or planted with bay rum trees; but on the whole during the colonial period, the inland estates were doomed by their ‘iffy’ conditions for growing either cotton or sugarcane. The sugar works at Misgunst are crude, and date to the early settlement period. They were in place by 1736 and were probably upgraded around 1769, when the property was purchased by Dedrich Kervink, who also owned Maria’s Hope and Pasquero. On approaching the estate, you first spy the factory ruins to the right of the downhill trail as two flat areas. It appears that the earlier horse mill, built on higher ground, was later replaced by a second mill directly below it. The first mill was then dug out (the wild pigs love it here and are still digging it out!) and quick-limed in an effort to store water for use in processing sugar & rum. It may be, David conjectures, they were collecting water from the runoff of the field system above the works. The steep topography and speed of water cascading through the gut when it rained probably dictated the need for such a reservoir.

Society member Fiona Stuart stands at

Misgunt’s still. It was noted as “new”

in 1769, with 2 copper kettles, a

molasses tank and the equipment for

sugar making.

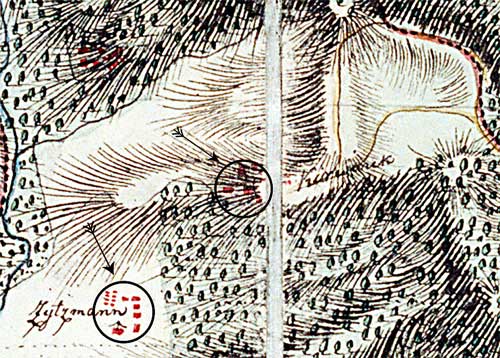

Detail from 1780 Oxholm map showing

Estate Misgunst, labeled “Kerevink” and

with Parforce being identified

as “Zytzmann”.

There were four well-documented industries practiced by St. Johnians during the post emancipation era. Raising cattle, which required few people, and fishing/seamanship were two. Working the land for provisions or for charcoal for use on St. John and export to St. Thomas was a third category. There are many coalpits along the trail and the heat from continual use has hardened the clay-like soil solid.

The fourth documented industry was dismantling old ruins for resale to the building trades. Hardwood timber, scrap metal and machine parts, and old brick were primary targets. By comparing a 1769 inventory of the Estate with what we see on the ground today, we see the results of this recycling effort. The 1769 mortgage inventory (see the Timeline of Misgunst accompanying this article as it appears on our website) notes a 40’x 20’ boiling house. Lief Larsen’s translation of the inventory notes that the southern wall of the boiling house is built of brick (or possibly he meant masonry) and the others are wooden; the roof is noted as shingled. What we encounter on the hike is the bare outline of this boiling house, as there are no remains of the wooden walls. The brick, along with the other recyclables, has been carted away.

We measure the size of the dwelling house, located on a knoll below the factory, at close to the 27 x 16 Danish feet that is documented in the inventory.

Misgunst is a true time capsule, as its works were never rebuilt or repurposed. When it was bought at auction by John Jennings in 1780, there was only one more year of sugar production. After Mr. Jennings died in bankruptcy in 1782, the estate was sold at auction to Frederich deBreton. It appears deBreton did what many consolidators did at the time—he purchased the estate not for the land but for its salvageable equipment and its slaves, a more valuable asset.

It is in 1782 that the estate name of Misgunst appears in the written record for the first time. Estates were often named after their owners or beloveds (Annaberg), for desirable virtues (Hope) or for site characteristics (Lameshur). However, it’s easy to imagine that misgunst, meaning unfavorable or misfortune, may have been commonly applied to the property as an epithet. After the first three owners (Riis David, Josias Valleaux, Johannes vonBeverhoudt Janzoon) died quickly after taking ownership, it could easily have been perceived as risky to reside at that ‘misgunst’ estate.

The people side of the inheritance timeline of Misgunst remained interesting in the 1800’s. The estate, an abandoned and unwanted property, is purchased by the owner of neighboring Bordeaux and Hope (also called Patience) plantations, Louis Michel, in 1798. Louis Michel’s wife (residing at Hope) expires in 1802, leaving son John, age 14, and a one year old daughter, Johanna. When Louis Michel acquires the Bordeaux plantation from the heirs of the Rev. Thomas Braithwaite, he apparently begins a relationship with Margaret Catherine Braithwaite, a former slave who had been the Reverend’s mistress. He installs her at the Misgunst estate house. When Louis Michel dies in 1838, his properties are inherited by his grandson John William Weinmar, except for a ten acre parcel of land and house that he gifts to his long-time companion Margaret Catharine Braithwaite and their daughter Catharina Michel.

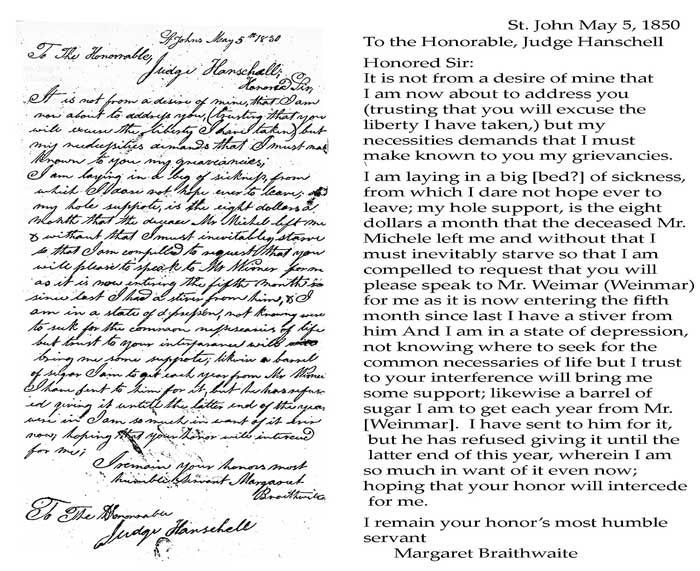

Margaret Braithwaite lives at Misgunst at least through 1850. Her impassioned appeal to Judge Henschell in Cruz Bay to intervene on her behalf with her distant cousin Mr. Weinmar for her annual barrel of sugar and eight dollars per month bequest shows that she was nearly impoverished, but quite literate and assertive. Her daughter, Catherina, at this time was in no condition to help her; as she was herself isolated and impoverished on her own property in Little Reef Bay. In 1863 Margaret’s grandson, John Knevels, reports the death of Margaret Braithwaite at his home in Coral Bay. Depending on the source, she was anywhere from 96 to 119 years old, and if the 1860 census of St. John is correct, she had been born in Africa.

What happened to Misgunst? Around 1910 Count Castenkjold assures its anonymity. He purchases Margaret Braithwaite’s ten acre parcel from Thomas Francis; he purchases the remainder of Misgunst, Hope and Pasquero from William Henry Marsh, and he acquires Cabrithorn and Great and Little Lamesur from Richard Penn. This consolidated property became one of the first large tracts of land given over to create the St. John National Park.

See the related items:

[Misgunst]

| Resource | Title | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Article | Estate Misgunst Meander | Swank, Robin |

| Estate Misgunst | Qtr=Reef Bay. Owner=Michell, L. Crop=Sugar. |