African Roots Project Reprise–St. John Emigration to St. Croix

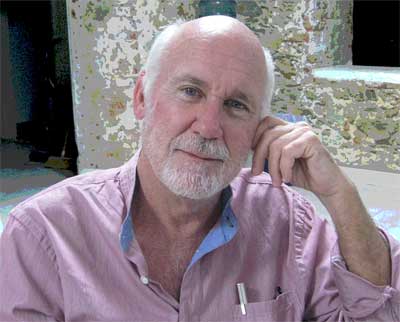

The African Roots Project‘s noted historian George Tyson summarized both the history of the project‘s database build and its exciting uses at the Society‘s March membership meeting.

(Presented by George Tyson, summarized by Robin Swank)

The Virgin Islands Social History Associates (VISHA) initiated the St. Croix African Roots Project (SCARP) in 2002 in order to investigate the population of St. Croix before and after emancipation. Although people from North America, Europe, the Caribbean, India and elsewhere came to St. Croix, the project‘s focus was on Danish West Indians of African descent. As a first step toward carrying out the research program, VISHA began creating a very large database of individuals living on St. Croix during the period of Danish rule (1734-1917). Production of the “St. Croix Population 1734-1917 Database” is now nearing completion, thanks to funding provided by the Carlsberg Foundation of Denmark, the Solar Foundation of Denmark and, most recently, the U.S. Department of the Interior. More than fifty of the Society‘s members warmly welcomed back historian George Tyson at our March meeting, to give us an update on the Database and its potential uses. Presently, 1.8 million individual entries extracted from historical records found in Danish, American and Virgin Islands archives comprise the database. These records include church and census records, slave trade registers, plantation inventories, vital statistics, immigration records, detail lists of enslaved Africans compiled for tax purposes, mortgage and title records. However, the database is clearly more than just a compilation of data for scholarly research; it is a rich resource for reconstructing life stories and family histories, which can frequently be traced to particular locations and ethnic groups in Africa. Mr. Tyson displayed census data from 1857 to 1911, Moravian Church records (where Africans self-identified their ethnicities), and other records which collectively yielded the story and family tree of the Finch family of East End St. John. The Finch family, some of whose members originated in the British Virgin Islands, moved to St. John where they acquired land in Coral Bay and immigrated to St. Croix, where their descendants are now prominent judges, engineers and entrepreneurs.” During the presentation, this database ‘product’ was enhanced by two members of the Finch family in the audience, who helped translate phonetic misspellings (a common historical problem) of their family‘s names by Germans, Danish and English record keepers into names that they knew. “The stories of the families of our islands,” he observed, “can only be fully told through all the documentation relating to the entire family of islands that comprise, beyond political designations, the Virgin Islands.” With a little data mining, the Database also gives up details about the movement of individuals between islands. Sources for documenting inter-island movements during the 18th century are limited, but Mr. Tyson used the Land Tax Records (Mariklerne), Slave Lists, inventories, censuses, police records and the Burgher Brief protocols (business licenses) from the Database to produce rosters of individuals who migrated to St. Croix from St. John at various points in time. Tyson noted that surprisingly few individuals emigrated from St. John in the wake of the 1733-1734 slave revolt. Audience members recognized some of those early émigrés from the 1735-1738 time period— Frederich Moth, Adrian Charles, Ditlev Madden (also written as Madsen), Cornelius Bodker, Gerert DeWindt, and Dines Silvan (Dennis Sullivan). James Barry, Adrian von Beverhoudt, Jacob Bufferon, Joseph Dreaker, and Cornelius Stallardt were documented as going to St. Croix between 1740 and 1745. Enslaved individuals from St. John, like those who came from Africa, were often identified by a geographic marker attached to their first name, such as “Mary St. John, or “Ebo Molly”. Thus, many enslaved St. Johnians can be discovered among the nearly 750,000 slave list and inventory entries found in the St. Croix Database. Mr. Tyson‘s research showed that following the termination of the Danish Slave Trade at the end of 1802, many St. Johnian slaves were moved by their Crucian owners to work in the more lucrative canefields on St. Croix. The people caught up in this forced migration were usually brought in small groups, so they could be classified as “domestic” slaves, thereby avoiding the prohibition against mass sales and removals of entire slave communities. By this means, the enslaved populations of several St. John plantations were decimated. For example, between 1807 and 1814 the enslaved population of Sieben-Mollendal plunged from 127 to 0, as members of the Rengger, Armstrong and Vallade families periodically replenished their Crucian plantations with St. Johnian laborers. Most of these St. Johnians ended up on Estates Hermon Hill and Mary‘s Fancy, where they and their descendants can be followed in censuses, inventories and other such entries in the Database. Other St. John plantations that lost laborers and families to this inter-island slave trade were Herman Farm/Chocolate Hole/Great Cruz Bay (owned by the Heyliger family), whose enslaved population dropped from 114 to 76 between 1810 and 1817; Little Caneel Bay (owned by the Sempill and Ruan families), which lost 56 slaves between 1819 and 1830, and Carolina (owned by the Schimmelmann family) whose slave population fell from 202 to 168 between 1815 and 1816. After Emancipation in 1848, small numbers of St. Johnians voluntarily moved to St. Croix, some to find work in the towns of Frederiksted or Christiansted, some to work in the canefields, some to reunite with families or loved ones. According to census records found in the Database, the number of St. Johnians on St. Croix grew from 51 in 1850 to 73 in 1870 and then gradually fell off to just 29 in 1911, a decline reflecting the general decline of the Crucian plantation economy and the Crucian population during the last decades of Danish rule. Mr. Tyson pointed out that because of the cost involved, the Database does not yet contain the best set of records for researching inter-island movements before and after Emancipation – the voluminous reports of passenger arrivals and departures kept by the police on all three of the Danish West Indies. Hopefully, these Police Report records, which are found at the U.S. and Danish National Archives, can one day be incorporated into the Database. What‘s next? Mr. Tyson concluded his presentation by stating that after VISHA finishes the St. Croix Population Database early next year, it intends to start compiling similar databases for St. John and St. Thomas. He reinforced that it was important to also incorporate documentation from the British Virgin Islands and Vieques, since people and families moved frequently among all of these islands. The St. Croix Population Database will start going on-line this summer at two locations, for a fee at www.ancestry.com, which is also providing the value-added service of digitizing the original documents, and for free at VISHA‘s own Website. Available first will be approximately 350,000 entries from all eleven Danish West Indian Censuses compiled between 1835-1911, several free-colored censuses and the Emancipation records of 1848. The remaining records will be added, after they have been verified and standardized, over the next nine months. The St. John and St. Thomas records will be next, and Mr. Tyson expressed his hope that VISHA and the St. John Historical Society will collaborate in accomplishing the St. John work. Professional and amateur historians and those on a personal search for their roots will soon find an amazing database at their disposal, thanks to the bureaucracy of the Danes, the zeal of the Moravian and other churches, the generosity of public and private funders, and especially the unceasing efforts of George Tyson and his colleagues.