The Testimony of William Blackstock [A True Story of Piracy and Buried Treasure on Norman Island]

(The following story is true. It has been wholly compiled from primary archival sources: no names, dates or particulars of the case have been changed. Any constructed details were added solely out of well informed supposition and a studied understanding of the places and events portrayed.)

Vice-Governor of the Danish West Indies Christian Suhm reached impulsively for his snuffbox and took a liberal pinch of the fine Virginia cut that was his preference. Having thus regained his composure, Suhm settled back in his chair and squinted to bring the page before him into better focus. Despite flattering salutations and assurances of respect and friendship, the communication delivered by Captain Fraser of the British sloop Otter had induced an immediate sense of prickling anxiety. Any and all negotiations with the English called for utmost diplomacy, not only in light of the long-standing distrust shared by the Danish colony and its British Virgin Islands neighbors, but also the barrier of language, which effectively distanced the two colonial holdings to a far greater degree than the three leagues of azure waters that lay between them. Adding to the delicacy of the situation was Captain Fraser’s insistence that the Honorable Gilbert Flemming, Lieutenant-General and Commander in Chief of all His Majesties Leeward Caribbean Islands in America — presently on the island of Tortola — expected nothing less than a prompt and favorable response to his request for cooperation in this matter.

From the stiff-handed script of Flemming’s message, Suhm could gather that at issue was an act of piracy committed by a North American sloop under the command of an Englishman, one Owen Lloyd. Raising an eyebrow, the Vice-Governor reflected that he knew the vessel in question well; she had lay at anchor in the harbor for some weeks within easy musket-shot of his chambers in Christiansfort. As to any particulars concerning the ship or its crew, he would now be obliged to order an official investigation — a touchy situation in the port of Charlotte Amalie, where questions concerning the disposition of cargoes or the whereabouts of strangers seldom met with a favorable response.

Duty bound to acquaint himself with the details of the case, the Vice-Governor set aside Flemming’s letter and carefully untied the silk ribbon securing a bundle of documents that had accompanied the communication. On the first page, a bold heading proclaimed: The Examination of William Blackstock this 26th day of November, 1750, on board the sloop Christian at sea.

Regardless of Suhm’s difficulty with the English language, the tale of piracy, greed, and hidden treasure revealed in Blackstock’s deposition, was to command the Vice-Governor’s attention well into lamplight.

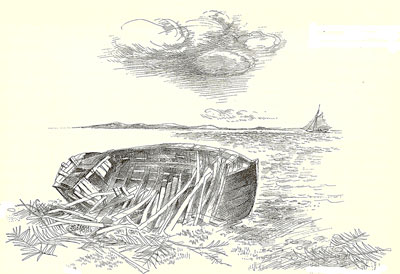

As in any good tale of piracy, William Blackstock’s narrative begins in a tempest: Freshly provisioned and loaded, only days out of Havana bound for Spain, the Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe had been separated from her convoy by a gale that left her dismasted and rudderless. Wholly at the mercy of the seas. In this hapless state an English merchantman came upon the Guadeloupe, and, upon inducements by the Spanish captain, towed the stricken frigate to safety behind the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was there, straining on her rode in the steep chop of the Pamlico Sound, that Blackstock first laid eyes upon the vessel that was to be his undoing.

William Blackstock, who also went by the name of William Davidson, was born in Dumfries, Scotland. A mariner by trade, he had sailed out of Rhode Island at the end of September, 1750, and put in at the Ocracoke Inlet on or about the 1st of October. The appearance of the Guadeloupe only days before Blackstock’s arrival had garnered much attention along the islands of Cape Hatteras. All eyes, it would seem, were on the storm-damaged ship, and throughout the waterfront taverns and smoky beachhead encampments of the inlet pilots, there was much talk and drunken speculation as to the nature of her cargo. Fueling this chatter were the actions of the Spanish captain, who had immediately hired two stout sloops — one out of New York, the other from Boston — and brought them alongside the frigate. Under secrecy so tight that even the masters of the sloops knew nothing of their cargoes, the Spaniards unloaded the contents of the Guadeloupe and packed it securely in the holds of the hired vessels. Manned by the Spanish crew, the loaded sloops were preparing to make way for Virginia when their progress was thwarted by a detachment of British troops under the command of a smartly uniformed major. In no uncertain terms the officer ordered the Spanish captain to accompany him to the town of New Bern some fifty leagues distant, where the Spaniard was to explain his intentions to the governor and give good reason why his ship had broken bulk without the proper authority. Reluctantly the captain complied, leaving his crew confined to the Guadeloupe, and the two heavily laden sloops unattended. For the dark-hearted sons of Neptune that frequented the farthest reaches of the Pamlico, so tasty a pair of prizes could hardly have been imagined.

When Owen Lloyd first approached him with a proposition to steal-away with the two sloops, Blackstock made light of the subject and passed Lloyd off as an idle schemer. But, with the departure of the Spanish captain for New Bern, it became clear that Lloyd and his associates had resolved to make good their plan. Upon consideration, Blackstock gave in to Lloyd’s urgings and joined the plot. The conspirators were a hastily-assembled collection of salt-encrusted rabble from up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Among them was Trevet, a thickset Carolinian with a slow back-county drawl, who Lloyd had chosen as mate. And then there was James Moorehouse of Connecticut, a headstrong young Yankee; William Dames, a sharp-eyed Virginian; a shoeless old sea-dog by the name of Charles; and Owen Lloyd’s brother, Thomas, who at the stump of one knee wore a crudely fashioned wooden peg.

The plan that Lloyd proposed was a simple one. The group was to split-up into two crews: one commanded by Owen Lloyd himself, the other by his brother Thomas. At a given signal, the men would take control of the sloops and break for open water. The masters of the sloops were likewise in on the scheme, but it had been agreed that they would remain below deck until the vessels were well out of sight from land so as not to be implicated in the crime. Once at sea the crews were to steer for the West Indies, where Lloyd assured them they could easily dispose of the vessels and cargoes; after that, it would be every man for himself.

And so it came to pass, that on a hazy mid-October afternoon, William Blackstock found himself at the helm of a swift New England sloop under the command of Owen Lloyd, making a desperate downwind dash for the Ocracoke Inlet with a nimble Spanish launch in eager chase. Breasting the opening to the sound the crew heaved in on the sheets and settled onto a hard-driving reach that rapidly distanced them from their pursuers. Looking back, the men could make out the oddly sloping mast of the second sloop piloted by Thomas Lloyd, which sat soundly aground only a short distance from where she had lay at anchor.

Spurred onward by a crisp autumn nor-westerly wind, which soon gave way to brisk easterly trades, less than a week passed before a solitary peak was sighted on the horizon. The waters below the sloop grew increasingly light in color, and coral heads began to be visible beneath her keel. Standing off to gain deeper water, the men next observed a rugged headland jutting into the waves like the prow of some giant ship. Owen Lloyd, who had sailed these waters before, had now gained his bearings. “Santa Cruz” Lloyd confidently declared to the crew, “and yonder, Spanishtown.”

Leaning hard into the bulwark to steady himself, Lloyd stared studying the maze of hills and hummocks that slowly began to come into view. “And there” he bellowed, an arm outstretched as if in introduction, “Norman’s Island, as proper a place to share up a booty as any in the West Indies!”

It was evening by the time the sloop slipped quietly into a deserted cove on the lee of Norman Island. Weary as the crew may have been, no sooner had the sails been furled and the anchor set than all hands went about the task of inspecting their mysterious cargo. The first items to emerge from beneath the hatch were sixty bundles of moldy tobacco, which the crew disgustedly piled in a heap on the shore. Their spirits soon rose, however, when seventeen bags of indigo were hoisted from the hold, followed by one hundred and twenty bale of cochineal, each weighing some two hundred and thirty pounds, and all in good order. With the bulk of the vessel’s cargo removed, a tight-packed stack of heavy wooden crates were all that remained in the bowels of the hold. As the men crouched expectantly around the boxes, Trevet, the mate, leaned forcefully on an iron bar and peeled back the lid of the first container. Inside, the box was divided into three compartments, and in each compartment was a coarsely-woven sack secured by a pressed-lead seal. His heart pounding, William Blackstock pulled a knife from his boot and drew its blade across the top of one of the sacks. In an instant, the hold fell as silent as death, until someone uttered, “silver, bloody pieces-a-eight!”

In total the men discovered fifty-two chests of Spanish silver in the sloop’s hold. Fifty of the crates were identical to the first, each holding three bags, and every bag containing one thousand freshly-struck, eight-reales coins. Two larger crates, measuring three feet by two feet, and one-and-a-half-feet deep, were filled with “church plate” and other wrought silver. Wealthy men all, the crew set about dividing the booty. Five chests of coins went to Owen Lloyd as pilot, five went to Captain Wade as master of the sloop, and four went to each of the ten hands. The remainder of the cargo was divvied-up into twelve equal shares — except for the rotting tobacco, which was free to anyone who cared to claim it. All except one of the crew took their coins and silver ashore on Norman Island to bury them, while Lloyd and Captain Wade each kept one chest of coins on board and buried the rest. Feeling ill used by Lloyd, Blackstock and William Dames, who had earlier resolved to leave the ship at their first opportunity, were the only ones to remove all of their booty (silver and goods) to shore.

The sun had passed into the west when Blackstock, Dames, and old Charles finished concealing their loot and headed back to the bay. Upon reaching the beach the men were surprised to see a fisherman in a small boat alongside the sloop. Ducking behind some bushes, they watched as the stranger pushed off his cobble and began to pull away towards a point of land at the far end of the cove. Immediately upon the fisherman’s departure, Lloyd and the others raised the sloop’s sails and fled the scene, leaving Blackstock, Dames, and Charles marooned on the island. Without water or provisions the three had little choice but to hail the fisherman and appeal for help. His name was Thomas Walts, and so leathery a specimen Blackstock had never laid eyes upon — a cordial enough fellow though, and educated in numbers, to a degree. Little time passed before Blackstock and Dames were headed to the larger island of Tortola in Walts leaky craft, while Charles stayed behind on Norman Island to keep lookout.

Upon landing on Tortola Blackstock inquired as to where he might find the local commander, and he was promptly directed to the residence of Abraham Chalwell, president of the island council. With a mind to legitimize himself and lay formal claim to his share of the booty, Blackstock reported to President Chalwell that he had been put ashore by a southbound vessel at Norman Island, where he had landed twenty bales of cochineal, two bags of indigo and a quantity of tobacco, which was good for nothing. The merchandise, Blackstock said, had been salvaged from a wreck off North Carolina. After due consideration, Chalwell proposed that on the following day he would accompany Blackstock to Norman Island and inspect the goods, making certain that the tobacco was of no worth as claimed.

It was nearly midday before Abraham Chalwell’s boat put in at Norman Island with Blackstock and Dames aboard. The men noted with dismay that the previously quiet bay had taken on a far different character than it possessed the day before. A score or more sailing vessels now lay close to the shore, and half-again as many small boats were dragged up on the beach.

As they approached the land Blackstock caught sight of Charles, his arms flailing like a madman, dashing headlong down the bay in their direction. “Betrayed,” the old man shouted, “we been betrayed! Look now, they seizin’ the chests!”

Taking the situation immediately in hand, Blackstock urged President Chalwell to quickly follow him to inspect the cochineal, while Dames moved to head off Charles and silence his fool tongue. After finding the cochineal undisturbed, and in exactly the condition described, Blackstock and Chalwell proceeded to the north end of the bay where they found Charles and William Dames taking some shade beside the heap of rotting tobacco. Charles, whose sunburned face had become badly blistered, looked wearily up at Chalwell at the very instant the President’s brass-capped cane thumped squarely on the old sea-dog’s forehead. “Listen you rascal,” Chalwell barked, “if there is any money here bring it out. If you do, I will take care of it for you. Otherwise, I will leave you here and let these people take your life for it.”

A short time later the group returned to Tortola carrying with them six bags of silver coins that Charles had produced from a rock crevasse not far from the tobacco pile.

On the following morning, a shallop belonging to one Captain Purser of St. Christopher arrived at Tortola and President Chalwell made quick use of it to bring the cochineal over from Norman Island. Along with the dyestuff, the ship also brought three more bags of coins that Charles claimed to have “met” while loading the bales.

True to his word, Chalwell handed all of the recovered goods over to Blackstock, retaining only two bales of cochineal as a “present ” Blackstock then gave one bale of cochineal to the “collector of the port”, another to Thomas Walts for the service of his cobble, and yet another to Captain Purser for freight on the shallop. The remaining fifteen bales of cochineal and nine bags of coins, plus a handkerchief containing about four or five hundred coins, were divided equally between Blackstock, Dames and Charles. Additionally, Blackstock and Dames each kept their one-bag share of indigo, as Charles had left his aboard the sloop. Later, Charles and Dames sold their cochineal to John Pickering, Esquire, for one thousand pounds currency per bale, while the “collector” purchased Dames’ indigo.

A few days hence, Blackstock went to Norman Island with Thomas Walts to bring back his share of the “church plate”, but found that it had all been taken away. There had already been talk on Tortola that President Chalwell’s son had at least twenty bags of Spanish coins in his possession, and that Mr. Haynes, the “marshal,” had thirty bags, while a Mr. Jess was said to have a considerable quantity of “plate”. Convinced that there was nothing more that could be recovered, Blackstock and Dames purchased Captain Purser’s shallop for one thousand Spanish dollars and prepared to leave Tortola; but, upon petitioning President Chalwell for clearance, the men found their request flatly denied. The issuance of a sea-pass, Chalwell explained, went beyond his authority, and a meeting of the full council was necessary to consider whether Blackstock and Dames should be allowed to leave the port. Nearly a week passed before the council handed down their decision, and when they did it was determined that the shallop could only proceed under ballast — a situation that effectively forced Blackstock to liquidate his indigo and cochineal on Tortola before he could leave the island.

On the 14th of November, Blackstock and Dames finally set out from the British Virgins with Captain Purser and a Mr. Young as passengers, and an old Tortola “Negro” as crew. Although the ship’s papers gave her destination as North Carolina, the shallop headed first for St. Eustatius[1], where Purser and Young disembarked. There, while lying off the road at Oranjestad[2], Blackstock caught wind that Owen Lloyd had been apprehended and at that very moment was a prisoner in the island’s fort. From what little straight talk they could muster, Blackstock and Dames pieced together that after leaving Norman Island Lloyd and the crew had sailed directly to the Danish-held island of St. Thomas. There, the men sold off the cargo and abandoned the sloop, making a pact to never associate with one-another again. Soon after, Lloyd purchased another sloop and set out for the Leeward Islands, but word of his misdeeds preceded him. He had been immediately arrested upon setting foot on St. Eustatius.

The story of Owen Lloyd’s capture, as told to Blackstock and Dames by a loose-lipped Mulatto with one blue eye, was made even more troubling by the informant’s repeated references to Lloyd as, “a villainous pirate.” It was then that the two decided to go their separate ways. Dames, who longed for cooler waters, had a mind to take the first available berth on a northbound schooner and leave the West Indies in his wake; while Blackstock was reasonably sure that with legal title to the shallop, and a proper sea-pass from President Chalwell, he had a fair chance of steering clear of any trouble. That was, of course, as long as Owen Lloyd hadn’t given any names. With this resolve, Blackstock handed over to Dames four hundred and fifty pieces-of-eight for his one-half part in the shallop, and ordered the old “Tortola Negro” hand to put the homesick Virginian ashore.

By evening the shallop was driving hard under a full press of sail, the island of St. Martin off her starboard bow. His shoulder braced against the wheel, Blackstock gazed out into the setting sun “Nowhere on Gods own earth,” he declared only to himself, “do Satins fires battle so hard to consume the day.”

Before another night had passed, William Blackstock languished in chains: the unwilling guest of the Honorable Governor Gumbs of Anguilla. And as to the whereabouts of Dames, or any other members of the sloop’s crew, he really couldn’t say.

Postscript

It was estimated by a British Court that investigated this case that the total value of the cargo stolen from the Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe exceeded 250,000 Spanish dollars. Of the 150,000 pieces-of-eight said to have been buried on Norman Island by Owen Lloyd and his crew, some 57,000 have never been accounted for.

Footnotes

- St. Eustatius: also known as Statia, a Dutch island in the Leeward group, known for its active trade.↑

- Oranjestad: Primary port town of St. Eustatius.↑

Primary Sources:

- West Indies and Guinea Company, Letters and Documents, 1751, Correspondence: Flemming to Suhm, November 31, 1750 (Rigsarkivet, Denmark).

- West Indies and Guinea Company, Letters and Documents, 1751, Correspondence: The Examination of William Blackstock, November 26, 1750 (Rigsarkivet, Denmark).

- West Indies and Guinea Company, Letters and Documents, 1751, Correspondence: Suhm to Flemming, December 15, 1750 (Rigsarkivet, Denmark).

- West Indies and Guinea Company, Letters and Documents, 1751, Correspondence: Macdonald to Suhm, December 24, 1750 (Rigsarkivet, Denmark).

References:

- Isaac Dookhan, A History of the British Virgin Islands (Essex, Caribbean University Press, 1975).

- Daniel & Frank Sedwick, The Practical Book of Cobs [third edition] (Florida, D & R Sedwick, 1995).

- George Suckling, An Historical Account of the Virgin Islands in the West Indies (London, Benjamin White, 1780).

- The New Spelling Dictionary, Teaching to Write and Spell The English Tongue With Ease And Propriety (London, circa 1790).