Losing Ground

The heavy rains that have saturated St. John this year have caused major inconvenience for many residents—and terror and heartbreak for some who live in vulnerable areas. The most visible and dramatic effects of the inundation have been along St. John’s most costly and heavily engineered stretch of road: the section of Centerline between Bordeaux and Coral Bay.

As many of you know, this was a road that did not exist until the mid-20th century. As motor vehicles began to slowly appear on the island, U.S. military engineers, who had been stationed in the territory since WW II, assisted the local government in road building on all three islands. The old Centerline ran behind the north face of Mamey Peak before it formed a “T” intersection at King’s Hill, where one could descend to Maho Bay on the north, or, just as precipitously and quickly, to Coral Bay on the south.

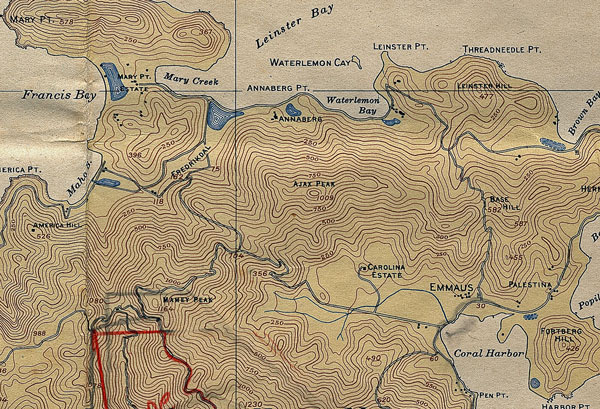

Detail from 1934 U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Map showing the old Centerline, which ran behind the north face of Mamey Peak before it formed a “T”intersection at King’s Hill, where one could descend to Maho Bay on the north, or, just as precipitously and quickly, to Coral Bay on the south.

Although the 1953 construction of the new road along the north face of the Carolina valley produced a long gentle grade, it also produced a deep cut through the fractured bedrock, across the face of very steep slopes. That road cut was to become much deeper when Centerline was widened and paved in the mid-1960s. In the memorably dry year of 1967, Governor Paiewonsky ceremoniously opened the completed route: two lanes, paved all the way from Cruz Bay to Emmaus. It didn’t last long.

Two consecutive years of unremitting rain–1969 and 1970–gave the island a combined total rainfall of 140 inches, culminating in a flood on October 7, 1970 that contributed 13 inches to that total.

The stretch of Centerline between Bordeaux and Coral Bay essentially collapsed. Along with dramatic landslides from above, there were numerous sections where the road fell down the hill, leaving one narrow lane against the cliff. Most people with four-wheel drive vehicles immediately went back to using the unpaved but safe King’s Hill Road at the back of the valley, although some continued to squeeze through past the crumbling gaps on the “improved” road.

Predictably, it took a long time to address the problem. In those days Centerline was not a heavily traveled road compared to the NPS-maintained North Shore. St. Thomas and St. Croix were struggling to cope with their explosive growth over the previous decade, and certainly not prepared to pay attention to Coral Bay, the “back of beyond” in the minds of most politicians. Only 190 residents were counted in the entire combined Coral Bay and East End Quarters in the 1970 census. Finally, with Federal disaster aid funding, an almost $2,000,000 contract was awarded to the large Vermont-based firm of Pizzagalli Construction. After numerous delays, they began work in the spring of 1973. Vast amounts of steel sheeting were installed, mostly below the road, and in many sections the road was excavated far into the upper slope to regain the missing width. Quantities of excess fill material were produced, leading to what may have been the island’s first environmental violation charges: the fill was dumped without permits in two mangrove areas in Coral Harbor (at the property owner’s request, apparently). The newly created VI Department of Conservation and Cultural Affairs issued a stop-work order, amid much governmental confusion as to which agencies were empowered to issue such orders. The Shoreline Alteration Bill, prohibiting the un-permitted filling of shorelines and saltwater wetlands, had been passed into law just a few months before, introduced by Senator Virdin Brown and co-sponsored by St. John’s Noble Samuel.

The re-construction project proceeded speedily through the exceptionally dry period of late 1973 and early 1974. Just as Pizzagalli neared completion on eastern Centerline, the autumn of 1974 brought more torrential rain—36 inches in the four months from August through November. More Federal disaster aid was forthcoming. And more violations from Pizzagalli—Washington withheld a final $400,000 payment until the construction firm removed the huge pile of rocks and fill it had “stored” at the edge of Coral Harbor’s mangroves. The Centerline flood repairs were finally completed in late 1975.

Sources:

- Virgin Islands Daily News 1969-1975

- National Water Summary: Floods and Droughts, U.S. Virgin Islands, National Geological Survey 1988-1989

- Rainfall Records for Cruz Bay and Caneel Bay St. John, from Climatological Data The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, and Unpublished Records.