Crystal Blue View of Tektite II

(On November 6, 2010, the St. John Historical Society and Cleans Islands International, which manages the Virgin Islands Environmental Resource Station (VIERS) for the University of the Virgin Islands, co-hosted a 40th anniversary commemoration of the Conclusion of the Tektite II project at VIERS. Don Near is a long-time Interpretive Ranger at Virgin Islands National Park. Don wrote this article for an internal Park publication and we wanted to share it with Society members.)

Tektite Museum at VIERS with the sign welcoming back returning aquanauts.

It was the summer of 1969, arguably the end of the most turbulent, ideological, take-action, yet inward thinking, decade of the 20th century. Rising to second place on the Billboard chart that June was the Youngbloods’ iconic anthem of the hippy generation that so helped to define the peace, love, dope (and hope) of the ‘60s, “Get Together” (C’mon people now, smile on your brother, ev’rybody get together, try to love one another right now).

JFK, brother Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated, civil rights were won on paper but without intense struggle for that equality. Feminism was on the rise as was the U. S. involvement with the Vietnam War. The GTO was the hottest “muscle car” around. I was about to enter 9th grade.

It was against this back drop that Bruce Schoonover spoke on November 6th, 2010 at VIERS in remembrance of the official end, 40 years to the day, of the Tektite II mission that, along with its predecessor, Tektite I, put Lameshur Bay on the world map, all those years ago.

A main goal of the Tektite program was to determine whether prolonged living in and working outside two conjoined pressurized metal cylinders on the bottom of Lameshur Bay was feasible. Bruce’s Power Point presentation was both informative and insightful. I’ll do my best to hit the highlights of the wealth of information that he, as well as a later panel of actual aquanauts, set forth to the 70 plus attendees in the VIERS conference tent. Alas, I cannot share with you the tremendous film footage and photographs that were shown.

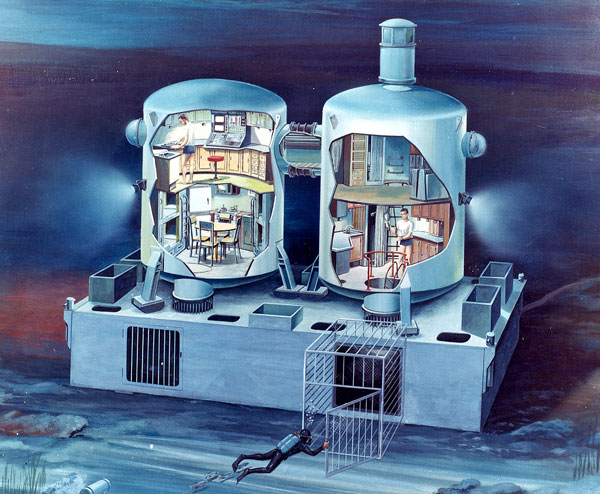

Rendering of the Habitat—consisting of two 18’ tall by 12.5’ wide cylinders-connected by a flexible tube and mounted on a base. Home for the aquanauts 49’ below the surface in Great Lameshur Bay.

In the height of the cold war, Russia had launched Sputnik I, the world’s first man-made satellite in 1957. If the Russians could launch one satellite then more could follow with nuclear warheads. Khrushchev had already denounced the U.S. and had implied that all of its children would soon live under the rule of Communism. So amid the building of bomb shelters across America, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the U.S. raced to overcome this strategic advantage and in a few short years formed NASA and exploded into the space program. The world power struggle had taken yet another twist and since the world’s oceans were as mysterious and alien to us in many ways as the solar system, exploring the seas became practical to NASA for a variety of reasons as well. This is where Tektite I comes in.

NASA wanted to see the medical and psychological effects of confined and prolonged isolation on human astronauts, as did the Navy with aquanauts. The Department of Interior was interested in what resources could be found in the ocean’s depth and the Missile and Space division of General Electric would build and equip the underwater habitat to facilitate it. The Navy and Department of Interior (DOI) also wanted to test the theory of “saturation diving,” which in short meant that divers could stay submerged for prolonged periods without periodic decompression as had been the norm… The significance of this was, if true, undersea exploration could be extended and expanded exponentially.

So in a historic 60 day mission starting in February 1969, four aquanauts proved that they could live encapsulated 49 ft. beneath the surface and explore the outside waters any time and for as long as they wanted as long as they waited for 19 hours and 22 minutes in a decompression chamber, one time, at the end. Interestingly, this magical number had to be arrived at and ultimately adjusted by trial and error experimentation with human support divers. In any event, other than some minor rashes and ear infections, there were no major medical problems and the scientists, who were continuously monitored by video cameras, showed no signs of seriously freaking out. The mission was a success but proved to be too short for any comprehensive scientific research to be conducted. Hence Tektite II the following year.

Dick Prince, program manager for NASA, poses with “aquanettes” Rene True, Peggy Lucas, Alina Szmant, Syliva Earle and Ann Hartline. Alina shared her memories during the commemoration.

Tektite II, unlike T-I, would last far longer overall (April through November,) encompass eleven individual, 13-20 day missions, each with five-person crews. In all, 54 marine scientists were engaged in a myriad of marine research studies. Tektite II also included the first all-women team (since mixing the sexes was ruled out) that understandably received the most attention in the world press. Ironically Tektite II as a whole was said to have been largely ignored by interests in Washington D.C., but the on-going fascination of the “aquababes” (a.k.a. aquachicks, aquagals and aquanaughties) got them not only in magazines and newspapers but also on TV, in a ticker tape parade and a lunch at the White House with Pat Nixon and Imelda Marcos, as related in a separate presentation by one of the aquanauts in attendance at VIERS, Dr. Alina Szmant. She also told of the success they had down in the habitat of being allowed to put up a shower curtain to shield the ladies from the prying eyes of the men monitoring them up above on the support dock—complete with a Playboy pin-up taped to the outside.

Also speaking at VIERS was one of the four Tektite I crew members (and marine science coordinator for T-II), John Van Derwalker, who commented that he thought the all female team was the most successful of the bunch in terms of the amount of work that they got accomplished. It could be suggested that they had the most to prove because they were women, but Van Derwalker, Dr. Sylvia Earle, another now well known member of the female crew (speaking on film) and Dr. Szmant all agreed that they probably were also the most motivated for a variety of reasons.

Despite the successes of the Tektite II missions, it was operating on a “shoe-string” budget compared to T-I. Of course both missions had to contend with the remoteness of the site and the relatively limited infrastructure of 1969-70 St. John. Just supplying water to arid Lameshur Bay was an adventure. “Pimpy” Thomas delivered water, in 800 gallon loads, via an old World War II truck and sometimes had to make several trips a day, which we can assume took a couple of hours each way. It would have really been an effort in October of 1970, as according to lifetime resident Eleanor Gibney, it was the wettest October in the past century and over two-thirds of Centerline Road coming into Coral Bay was closed to one lane and in various states of disrepair and landslides for two months.

Pimpy was contacted by phone where he worked at the Fire Station in Cruz Bay, either for water or to bring out the other members of his steel pan band to entertain the 70 or so gung-ho citizens of the bustling base camp, mostly young men who came from all walks of life, including college students, divers from the Highline Community College in Washington state, DOI officials, cooks, handymen, medical techs, members of the press and often the next aquanaut crew in waiting. The fiscal constraints meant that some of them were not necessarily getting paid much but it was a good chance to spend some time in the exotic Virgin Islands.

The base camp for the entire operation, today’s VIERS cabin complex, was constructed for Tektite I by Navy Seabees over a three-week period in late 1968. By the latter part of Tektite II, there was even a bar operating in base camp, called Hurricane Hole, a little plywood shack that served up such concoctions as the “re-breather,” basically your standard rum and coke, as well as the “baralyme” that was wine mixed with 7-Up and the dregs of any other liquor bottles on hand. Officially there was to be no alcohol or recreational drugs (other than tobacco that couldn’t be lit in the air pressure of the habitat anyway) inside the habitat, but the story goes that while still in dry dock in Philadelphia before being shipped down to St. John, the structure was secretly provisioned with spirits stashed away in air condition ducts and the like for the benefit of the Tektite I aquanauts.

But it was a real can-do—work with what you have—attitude that prevailed in all areas of the Tektite II mission. Six running jeeps were soon reduced to two because of the harsh road conditions and John Van Derwalker recounts how one NASA scientist reconditioned a carburetor making do with a pencil eraser to polish the points.

Tektite I & II aquanaut and marine science coordinator for T-II, John Van Derwalker provides attendees with a number of fascinating stories during the Q & A period.

During the question and answer segment of the presentation, I asked the panel what, if anything really stuck out as the most unusual or spectacular fish or other marine creature they might have seen in all those hours under water. Van Derwalker said that more than anything it was the spatial sharing of the reef that most impressed him. There was a moray eel right out the hatch that left a particular hole every night only to have its space occupied by a triggerfish. And they would change again in the morning. He would see the same type of thing happening time and time again, like a squirrel fish trading with blue chromis. Apparently the five telephone and auxiliary air tank equipped way- stations placed strategically around the ocean bottom were never used for refuge from large or dangerous sharks. He also conceded that only near the end of extensive studies on lobsters surrounding the habitat were any scrutinized for their taste and texture.

The Tektite project was not without its scarier moments. Van Derwalker once passed out and sank into the bottom of a deep reef canyon when his re-breather conked out, unbeknownst to his dive partner who was slightly ahead. He said it was divine intervention that he hadn’t drowned. And one of the Navy Seabee divers recounted the time some dynamite blasting was being carried out in a quarry by Cruz Bay. I’m not sure whether he was referring to the water catchment in back of Caneel or at the dump, but it sounds as if a good deal of the west end of St. John would have been blown to smithereens had not some quick revelations and footwork taken place by a nearby shed storing tons of explosives.

Through all the trials and tribulations, successes and disappointments with the two Tektite projects, I’m thinking there was one thing that drew everything in like a magnet, held it all together and helped to preserve this unique slice of history. To borrow from Tommy James and the Shonedells, it was the crystal blue persuasion of the magical depths of the Caribbean Sea off of Beehive Cove, around the bend from great Lameshur Bay.

(Members are encouraged to visit the Tektite Museum located at the VIERS base camp location. This museum, which contains a huge stash of mementos and memorabilia from the Tektite missions, is the brainchild of Randy Brown, President of Clean Islands International, the organization that operates VIERS on behalf of the University of the Virgin Islands.)