The Forest Island

When the first Europeans landed on St. John, did they see a dramatically different landscape and vegetation from what we observe now? In the absence of detailed reports from that time, we have to make a lot of educated guesses. The early accounts that do exist are often misleading, perhaps due to the same kind of confusion of plant names that still exists today.

Although the forests and dry shrub-lands of the island have certainly been altered by the human activities of the past 300 years, there has been no large- scale extirpation (eradication) of native plants. How do we know? There are at least 646 species of indigenous plants on St. John, and this diversity compares very favorably with the least historically disturbed dry forests of the Caribbean.

Climate has always limited potential forest cover on the island to an extent; droughts and hurricanes of devastating degree recur several times a century. Before plantation agriculture, the soil on slopes would have been deeper and thus retained more of the rainfall — but there is no evidence that actual rainfall was higher over any significant period in the past.

Almost certainly, the moister sections of St. John (guts, coastal plains etc.) had massive trees, taller than almost anything we see now. Many of these trees were desirable timbers (red locust, mastic, satinwood, gre-gre, bulletwood etc.). The drier forest of the south and east probably contained quantities of short but stocky lignum vitae, one of the most valuable woods of Tropical America, now threatened throughout its original range, including St. John. All of these are hardwoods that take centuries to attain optimum size; some became rare and are now slowly reappearing. In the absence of annual growth rings, we can only estimate the ages of trees from modern observations and records.

Almost certainly, the moister sections of St. John (guts, coastal plains etc.) had massive trees, taller than almost anything we see now. Many of these trees were desirable timbers (red locust, mastic, satinwood, gre-gre, bulletwood etc.). The drier forest of the south and east probably contained quantities of short but stocky lignum vitae, one of the most valuable woods of Tropical America, now threatened throughout its original range, including St. John. All of these are hardwoods that take centuries to attain optimum size; some became rare and are now slowly reappearing. In the absence of annual growth rings, we can only estimate the ages of trees from modern observations and records.

The driest land was certainly always dry, and some of this habitat is probably virtually untouched by events of the past 500 years, as we find numerous rare plants here, including many found only in the VI, and at least one found only on St. John. The hardwood trees of these areas grow very slowly indeed, and larger specimens probably have been here since the Tainos still occupied the island.

We know that the British from Tortola had been lumbering St. John up to the time the Danes officially settled in 1718. What happened after Danish arrival is open to conjecture, but most scholars of the island’s past agree that the plantation era caused considerable clearing of original forest, but no more than 50% of the cover was removed at any one time. Thus, when land was abandoned, as it frequently was with the tides of time and fortune, there were always native trees nearby to provide seeds to re-colonize the clearings.

Although traditional accounts of the island’s history implied that agriculture never fully recovered from the 1733 rebellion, we now know that the heyday of sugar production here was not until the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Surprisingly, we find many references to the forests of St. John right through this period. Starting with Peter Lotharios Oxholm, who produced the invaluable map that shows the cleared and forested areas of the island at the end of the 18th century, we find writer after writer extolling the wildness, and usually the beauty, of the wooded hills. Oxholm himself wrote in 1780: “…large trees and mountains eliminate all possibilities for passage…” In 1807, Danish Naval Officer Hans Birch Duhreup said: ”…St. John is undeniably the most picturesque of our islands and the most beautiful scenery I have ever beheld… The return trip at midnight through dense woods the most beautiful I have ever ridden.”

In the 1830’s the Danish naturalist A.S. Orsted visited the three Danish West Indies and was captivated by the natural beauty of St. John. He writes at great length about the vegetation in “Islands of Beauty and Bounty”, the text that accompanied six plates in “Danmark”, a sort of coffee-table book of the time on Denmark and its colonies. The St. John text contains this interesting observation: “It is not only the more untamed, romantic mountain terrain that makes St. John so different from the other islands, but since by far the major part –11/13—remains uncultivated, its mountains and valleys are overgrown with forests and brush so that we have an opportunity here to acquaint ourselves with the vegetation in its original form, while on the other islands it is mostly imported plants that meet the eye everywhere.” This was written over 150 years ago, at about the time of emancipation. The island’s population in 1846 was 2450, by 1900 it was 925 and it did not rise above that level again until the 1960’s.

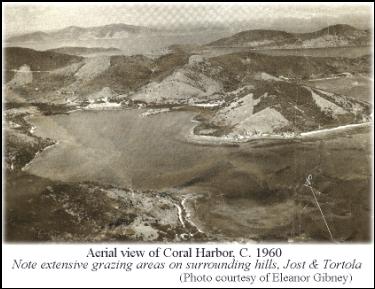

The post-sugar era on St. John saw the emergence of four land-based economic activities: cattle ranching, charcoal burning, bayrum oil extraction and basket making. Interestingly, 3 of the 4 activities were reliant on indigenous forests: mostly native hardwoods for the charcoal; the indigenous bayrum tree (St. John trees were famous for their fine scent); and hoopvine and wist for basketry. Many of the former sugar estates converted to cattle operations: at Caneel Bay, Cinnamon, Carolina, Lameshur, Susannaberg, Mary Point… the 1932 St. John cattle census lists 1243 head on the island. Probably at least as much land was kept clear by cattle as by sugar production formerly, and most of these areas still contain highly disturbed vegetation today. Charcoal production in contrast was a surprisingly benign activity for the forest—most trees re-sprouted vigorously from their stumps, and we find many older trees that have been coppiced in this fashion. The areas where bayrum was actually cultivated are also still evident: on Bordeaux, at Cinnamon Bay and sections of Mollendahl and Hawksnest.

The post-sugar era on St. John saw the emergence of four land-based economic activities: cattle ranching, charcoal burning, bayrum oil extraction and basket making. Interestingly, 3 of the 4 activities were reliant on indigenous forests: mostly native hardwoods for the charcoal; the indigenous bayrum tree (St. John trees were famous for their fine scent); and hoopvine and wist for basketry. Many of the former sugar estates converted to cattle operations: at Caneel Bay, Cinnamon, Carolina, Lameshur, Susannaberg, Mary Point… the 1932 St. John cattle census lists 1243 head on the island. Probably at least as much land was kept clear by cattle as by sugar production formerly, and most of these areas still contain highly disturbed vegetation today. Charcoal production in contrast was a surprisingly benign activity for the forest—most trees re-sprouted vigorously from their stumps, and we find many older trees that have been coppiced in this fashion. The areas where bayrum was actually cultivated are also still evident: on Bordeaux, at Cinnamon Bay and sections of Mollendahl and Hawksnest.

Some of the island’s moistest areas that remained in use into the 20th century, like Cinnamon Bay and the lower Reef Bay valley, have returned to forest relatively quickly, although this is where we tend to find many of the weedy plants from elsewhere dominating the scene, such as the South American genip and the East Indian sweet lime. The genip is believed to be a Taino import that became commoner in the plantation era as a sturdy source of fruit and shade. Unfortunately it tends to seed in thickly and prevent the growth of other plants, perhaps through chemicals produced by the root system. Genip dominates many of the formerly cultivated guts, especially on the North shore. Larger genip trees, including many in Cruz Bay, are all well over 150 years old.

The dry lands of St. John tended to have less historic disturbance, since even cotton requires some depth of soil and protection from the prevailing easterly wind. Grazing, particularly of goats, has been the major altering force. Over time, the animals consume all of the young plants that are not poisonous or thorny, creating a vegetation cover of the most noxious species, both native and introduced. This is very evident in sections of the south shore, where maran and casha prevail. This semi-desert will recover very slowly from disturbance, even if goats are no longer present.

Somewhere along the line an aggressive “pioneer” plant was introduced from the mainland of Central America: the wild tamarind or tan-tan. The transfer may have been intentional (it is still promoted as a fuel and forage plant for the third world) but the plant soon did what it has done all over the tropics: occupied any land that had been disturbed or cleared. Eventually this sun-loving plant gets shaded out by taller-growing trees, but hurricanes and grazing animals can help keep it around for at least a century. Most of St. John’s former cattle lands are still heavily covered by this pioneer. From Bellevue looking across the upper Fish Bay watershed, one can pick out a solid patch of wild tamarind on a knoll, marking Sieben Estate, the cattle operation of Julius Sprauve Sr., sold to the nascent National Park in 1954.

St. John is unique among all the islands of the Caribbean today in having retained a large percentage of indigenous dry forest that is protected. Many of the fine hardwoods, such as satinwood and lignum vitae, are gradually regenerating. Every section of the vegetation can reveal clues to the land use and activities of the past: like so many aspects of the island, an astonishingly large and rich source of knowledge and enjoyment.

(Eleanor Gibney is on the Board of the SJHS, is a life-long resident of St. John, having grown-up at her family’s beachfront property on the North shore. She worked for 15 years at the Caneel Bay Resort and became its chief horticulturalist. Recently, she published her first book, “A Field Guide to Native Trees and Plants of East End, St. John U.S. Virgin Islands.” She is widely regarded as the premier tree and plant expert on St. John. She is married to Gary Ray, and they have two young children.)