Mary’s Point Hike

(By David Knight, summarized by Robin Swank)

SJHS President David Knight welcomed about thirty members to our December hike on Mary’s Point. We met at the Francis Boiling House on what was once the Betty’s Hope plantation, which straddles a strategic isthmus separating Mary’s Creek and Francis Bay. At the outset David informed us that he is going to lead us to several little-known estate sites, some of which were reused and built over throughout history; he proposes to share available documented historical fact, but cautioned that he will interweave it with sound conjecture — necessary because although there is much existing data, there has not yet been a committed effort on the part of the land owners (the National Park Service) to uncover the full story of these sites and the people who occupied them.

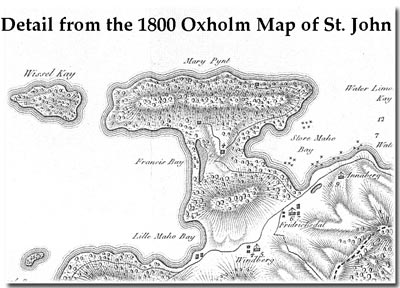

Betty’s Hope and Mary’s Point appear to have been parcels of land originally held by high Danish West India and Guinea Company officials during the early years of Danish settlement. Balancing the desirable east-west coastal shipping access of the isthmus with Mary’s Point’s and the general unsuitability of the land for agriculture (dry, windy, steep), it was not until the 1720’s, after the ‘best’ planting grounds were taken up as estates and a new generation of Danish settlers needed additional land, that the area began to be parceled out.

Already resident, the van Stell family was given the first controlling landholding on Mary’s Point. By 1733, there were 3 estates in the Mary’s Point area. Betty’s Hope, which straddled the south side of the isthmus between Mary’s Creek and Francis Bay, had its own estate house and factory complex should not to be confused with the Mary’s Point estate structures, although all were eventually merged as part of Annaberg by 1786-87.

Although a ‘Free Colored’ population had long been established on St. Thomas and St. Croix, the owner of the Mary’s Point estate, Franz Claasen, was among the first ‘Free-Colored’ plantation owners (ca. 1738 — 1780s) on St John. How did the Mary’s Point parcel pass from the van Stell’s in the 1720’s to Franz Claasen?? The van Stell family held the property through the 1733 slave rebellion. As originally reported by Pierre Pannet in his 1733 “Report on the Excreble Conpericy Carried Out by the Amina Negroes on the Danish Island of St. Jan in America’ (translated from the original French and published by Aimry P. Caron and Arnold R. Highfield), a band of rebels were headed to ravage Betty’s Hope. However, a loyal estate slave headed them off, saying he had already killed the owners. Jacob von Stell, who was ill and bedridden at the time, thus had the opportunity to gather his family and escape by boat, delivering the first word of the St. John slave Rebellion to St Thomas. After the rebellion, ca. 1738, the Company’s records show that ‘a loyal negro’ was given a parcel of land ‘in return for his help during the Rebellion.’ Franz Claasen’s land deed was recorded August 20, 1738 by Jacob van Stell and is corroborated by the almost-always accurate 1780 Oxholm Map.

“Rediscovered” several years ago and identified as a separate estate by historian George Tyson, the Oxholm map and original land deed clearly indicate that the boundaries of Franz Claasen’s estate cross the isthmus ‘sea to sea’ and that the ‘estate boundaries follow the sea-line.’ Oxholm’s map also displays that the adjoining beach at “Francis Bay” was originally named for the property owner, Franz [aka: Francis] Claasen.

Now skip forward three quarters of a century… to another story…

Post emancipation, poor economic conditions and the plantation owners’ reactive contract labor code had contrived to keep most former slaves on the estates. In the 1848 census, George Francis was listed among Annaberg’s most trusted enslaved laborers, but in the 1860 census his position was listed as ‘overseer.’ By this time he had married Hester Dalinda (ca. 1845) from the Munsbury/Frederiksdal Plantation and moved their family to Annaberg. Hans H. Berg, Annaberg’s owner, passed away in 1862, and granted George Francis outright title of a 2-acre parcel on Mary’s Point. When Mary’s Point came up for auction during Berg’s probate reconciliation, George Francis put a down payment on the estate. By the 1870 census, he was listed as ‘planter.’ In 1871 he purchased both Annaberg and Leinster Bay at a post-hurricane bankruptcy sale.

Why was a man named Francis again on Francis (Franz’) Classen’s ground? Is George’s last name “Francis” a place-name rather than a family name? Was it George’s ancestor who gave Francis Bay its name? Knowledge of local naming practices is key to documenting history and genealogy, David points out, as he talks through several possible answers to this question he points out that unlike in the British colonies, where a plantation owner’s name was often taken up as a surname by estate laborers, this practice was not widely adopted in the Danish West Indies except in the cases of a “blood” relationship. Names taken-up by both poor, or disenfranchised European settlers, as well as persons of African descent, were often based on designations of profession (Cooper), of places (Allberg), or whimsy (deWint [the Wind]), and, particularly in the case of the enslaved, a child would often carry his or her mother’s given name. The name Francis could also simply be a contraction designating an individual of French heritage, or the name might identify a place of specific interest to a person’s lineage — which could well be the case in George Francis’ situation.

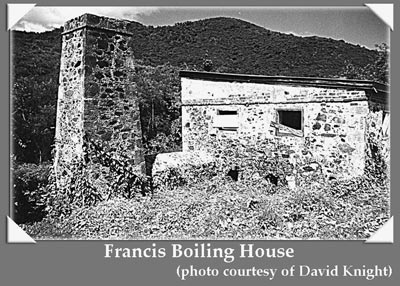

We do know that the stone Boiling House and Chimney, where we begin our hike at Betty’s Hope, were constructed by George Francis in 1874, soon after his purchase of the broader Annaberg Estate. Three cut coral plaques with the 1874 date are imbedded in the walls. This is most likely the last true sugar factory constructed on St John, a scaled-down version of the one at Annaberg. Tax records reveal that sugar was indeed grown at Mary’s Point during George Francis’ lifetime, but whether or not sugar was ever produced at the Francis boiling house is unknown as George Francis died soon after completing construction of the facility. A fourth cement plaque, bearing a 1911 date, commemorates the conversion of the boiling house to another use, probably as a more generic farm building.

As we walk north and uphill away from the Boiling House, David informs us that after George Francis’s death management of the estate was left to his third wife Lucy and their 5 children. The estate remained largely in pasture through the 1950’s when, Eleanor Gibney remembers that there were wild horses to be caught and broken, even though no-one would buy them. The community here remained an active one after Hans Berg parceled out his estate; Ethel McCully’s book, Grandma Raised the Roof, and some of Karen Olwig’s research document the communities’ history.

Pink-blossomed Coralita, a Mexican creeper, suddenly flows across the path. This sun-loving ‘pretty pest’, Eleanor informs us, was used to insulate earth-covered piles of wood being turned into charcoal. The ruins of the Creque family summer house, which appear to be second or third generation structure built over older Betty’s Hope estate house structures, are covered with this plant. The older yellow bricks, and the more recent green, cream and coral tiles and toppled decorative cement balustrades peer out from beneath a collapsed second story. The abandoned Creque commissary freezer and batteries lie side by side with some concrete around the cistern that appears to be the same vintage as the Boiling House below. There are outlying buildings, possibly old servants’ quarters built prior to the reclamation of the original estate house. Behind the house and around the path the re-growth of bush reminds us that time obscures both the history and physical sites from human memory, and that we had best hurry to gather the recollections of our living historians.

We continue upward. Through the thick bush we need to look closely to see that the whole ridge has been manipulated by man since the early 1700s. The rock flats, ledges, and open spaces need to be interpreted into the industrial plant it probably once was. Once this land was the site of an active and well-developed cotton plantation, indicated by the remains of stone-built slave cabins, house foundations and a storehouse (magazine) needed to keep the cotton dry after ginning. There is a large cistern, possibly constructed with recycled stone with gravity feed for the lower house and plantings. There is a large flat area, possibly a ‘bleach,’ where laundry was laid out and salted to dry. One can well imagine that the bush still holds many unseen components of industrial structures associated with activities such as the grazing of livestock — listed in the estate rolls cattle, sheep and goats — and the planting and processing of cassava and other provisions required to feed the estate.

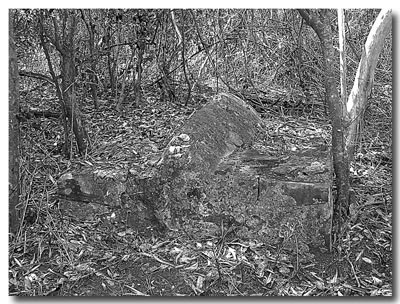

As for Franz Claasen’s estate house itself, a stone ring-wall foundation is all that remains, but it was most likely constructed with daub and wattle or half-timber upper walls and a palm, sugar-cane thrash, or grass thatch roof — all of which would have been plentiful. The image of the ‘grand estate house’ is clearly wrong-headed here, but the main house was two or more times greater in size than most of its contemporaries. In comparison to his peers, Fraanz Claasen was in all likelihood quite well-off, embedded in the upper strata of the Free Colored society of the time. According to his probate documents, upon his death in 1780 he owned 9 enslaved people, who appear to have been living as family groups on his plantation.

The entire area is difficult to interpret, David points out, because it is more ‘organic’ than a European-style straight-line plan; rock outcroppings are used strategically, areas cleared and materials gathered for one use have been strategically reused. The whole process speaks loads about the ingenuity used to live lightly with the land — everything was recycled.

After Franz passed, his wife and his daughter were given a prominent Free Colored curator, Peter Tameryn, to handle their estate. However, despite this and the matriarchal orientation of the Free Colored community, the lack of a son made it difficult for the family to retain their landed status. It is probable, David conjectures, that Claasen’s genealogy reflects the trend of the time, that the daughters of Free Colored families often ‘married up’ into the Creole or white plantocracy, thereby diminishing, rather than perpetuating Free Colored land ownership.

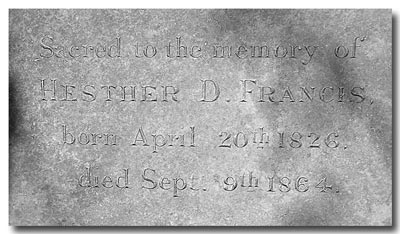

Continuing our walk, now staying strictly on a path through the cactus sucker-strewn ground (a sure sign of previous cattle-grazing, says Eleanor) and dancing around the fire ants, we visit two partial burial sites. The older grave is a quite formal raised European-style (i.e. not the flatter Moravian-style) marker of imported red clay tiles. This could be the gravesite of Franz Claasen’s first wife, but is more probably the gravesite of Franz Claasen himself. The more recent formal red brick structure is the grave of Hester Dalinda Francis, dated by a loose rather modern stone tablet — dated April 20, 1826-September 9,1864. These two markers are possibly indicative of a now overgrown multi-generational cemetery, but that is yet to be determined.

Full of information, we trek back to our automobiles. Driving home, we mull over all the things we have learned and are intrigued by how much we still don’t know. So, David… just who was Betty of Betty’s Hope anyway?

Excellent Bushwackers!!

Many thanks to the following bush-cutters who made our journey back in time a little less perilous —John Achzet, Peter Burgess, Larry Boxerman, and Weldon Wasson.

[Annaberg][Mary’s Point]