Botany Bay Estate–Our Trek to St. Thomas

(Assembled from David Knight’s 1/17/09 Handouts, his Timeline Notes on Estate Botany Bay, and Trek Dialogue, Summarized by Robin Swank)

Occasionally the SJHS sojourns far afield of St. John. On this Saturday, fifty members and guests journeyed to the far west end of St. Thomas to Estate Botany Bay, a private landholding of Warren H. Corning and his heirs from 1955 through 2000, and seemingly as remote today as it was in the 18th and early 19th centuries. David Knight, SJHS Board Member and Archivist, hosted this event. He drew extensively from his in-depth research conducted on–site and in Copenhagen while compiling a historical survey for the developers who purchased the estate from the Corning family in 2001.

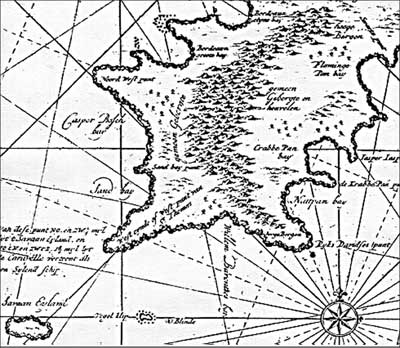

Detail from the earliers known overall map

of the Danish West Indies colony rendered

in 1719 from the Royal Library Map

Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark. Note

Caspar Busch Bay, currently named

Botany Bay.

Only some of the highlights of our Trek are assembled here. Please visit Botany Bay Notes 1/17/2009for the complete set of David’s Handouts and Timeline Notes on Estate Botany Bay. The title transition documentation is extensive and was one of the most difficult he has constructed, David says, because of the large number of parcels consolidated.

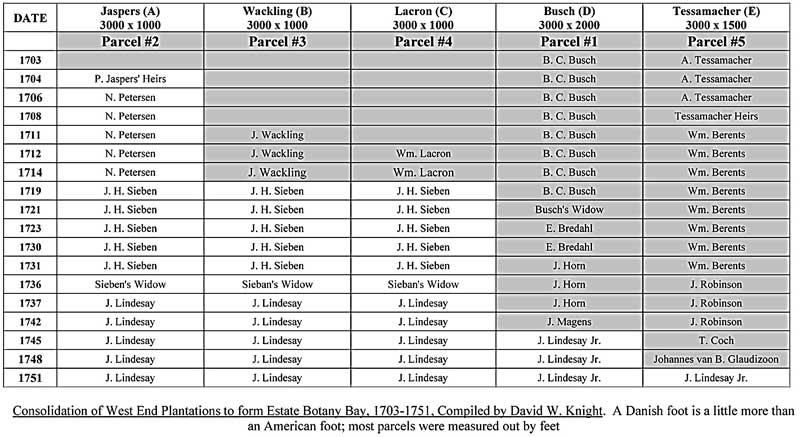

The story of the consolidation of west end plantations to form Estate Botany Bay begins with Balthazar Caspar Busch and A. Tessamacher. (Please see the insert, Consolidation of West End Plantations to form Estate Botany Bay, 1703–1751, following.) In 1703, each took up property in the west end, as colonists sought arable lands for the growing of produce and the raising of livestock in the unsettled frontiers of St Thomas. Their purpose seemed not so much to make a profit, but to grow some produce while covering their debts.

Balthazar Busch, noted David, was an interesting character ‘of a dark volatile nature.’ There is a documented dispute with neighboring landowner, William Barents, where knives were drawn, threats exchanged, and soldiers called. Barents (who subsequently took ownership of Tessamacher’s parcel) was hauled off to the fort, where he overcame the guard and then went to Busch’s house ‘with the intent of cutting off Busch’s right ear.’ There is also an intriguing isolated report at Busch’s death in 1721: “Caspar Busch committed the awful murders and cut his own throat.’ Although Busch took up the property in 1703, he apparently relied on his overseers and never lived at Botany Bay.

Another character in the chain of consolidation was Johannes Lindesay. Lindesay acquired a number of consolidated parcels by marrying John Heinrich Sieben’s widow. Before coming to St. Thomas, Lindesay was Commandant of St. Eustatius and was most likely involved in the Dutch port’s thriving business in illicit goods, most notably duty free slaves landed for transshipment under Spanish contracts. Officials were known to take a cut of the profits, and it can be assumed Lindesay was not innocent of that practice. He fell from grace in1728 after a deal he brokered resulted in the loss of 40,000 pesos of Dutch West Indies Company goods. He was imprisoned, but along with his two sons managed to escape to St. Kitts, then to Montserrat and then to the Danish West Indies. Within a year of his marrying the widow Sieben in 1738, the properties began to be listed in Lindesay’s name as his wife’s guardian. Within another year, however, despite the (conjectural) allure of a deserted remote property (to host illicit activities?), he and his household and 29 slaves left St. Thomas for St. Croix, leaving his West End plantation apparently unoccupied.

Throughout the 1700’s consolidation continued, accompanied by attempts at cotton farming, or growing cassava and other provisions. The laboring population continued to decline. The consolidation ratio for Botany Bay, David points out, is closer to 6:1 than the 3:1 ratio we normally see across the Danish West Indies. Many of the ‘blue collar’ owners had small subsistence parcels; abandonment, bankruptcy and death litter the ownership/title chain. The motive for consolidation was not only land acquisition, but also acquisition of recyclable or reusable materials and acquisition of the enslaved laborers. The death rates of the slaves far outweighed the birth rates on the remote western end, and the death and illness rates were exceedingly high.

The ocean–side sugar–works built by James Murphy and Owen Sheridan were cutting– factories of their

time. Although the process of sugar–making was similiar at both Annaberg and Botany Bay, the works are

configured quite differently, each using the topography of the land and gravity of efficinet production.

The single well in front of this factory may have been unable to provide enough fresh water to support

sugar production, or possibly (as documented at Hull Bay), the water may have become contaminated by

cholera, which remains tenacious in brackish water and would have been easily spread in the beachfront

area when the infected were buried in the laborers’ low–lying houses. One of the ‘coppers’ is currently

hosting a flotilla of water lettuce (Pistia).

In addition, the enslaved had a view of Vieques, Culebra, (and a mistier Puerto Rico), which meant freedom for any slave who could reach there and was willing to embrace Catholicism. Maronage (runaway) rates were high. By 1745 the loss of slaves to Puerto Rico was so high, that the DWI petitioned Puerto Rico for compensation. Pinguin (‘wild pineapple,’) which we saw thriving all through the bush, seems to have been planted not only as a fence, which we’ve seen on other estates, but as a widespread general deterrent to anyone passing through and to/from the isolated and mostly uninhabited west end.

By the time Nathaniel Alt owned the property (1778–1782), the estate’s length stretched from the island’s northern to its southern sea coasts. In 1783 Thomas Armstrong (the father of James Murphy’s wife), acquired the property and the enslaved population rose sharply; it became listed in the yearly tax rolls as a ‘sugar plantation.’ It was most likely during this period that the primary focus of the estate’s activities shifted from the dryer upland pastures and cotton grounds in the east–central section of the property, to the more ‘lush’ lowland valley that extends inland from the narrow coastal plane behind Botany Bay. The substantial upland ruins (which we did not see), David says, most likely represent the original West End plantation. Surprisingly they are not shown on any maps after the establishment of the sugar factory on Botany Bay in the early 1800’s.

Between 1801–1805 partners Jasper Rashleigh and Owen Sheridan converted the West End Plantation to a well–developed agro–industrial sugar estate and christened their upgraded property Botany Bay. Why did they name it Botany Bay? Eleanor Gibney, who conducted a Botanical Survey of the property at its purchase by resort developers in 2001, says that it is possible Murphy, an Irish renaissance man of sorts, could have realized the diversity and the rarity of plant life in the area and so named it; there is currently one orchid that is completely unique to the Spanish and US Virgins here. However, it is also possible the area was named in comparison with Britain’s remote Botany Bay in Australia. The website http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com reports that two British gentleman botanists landing there in 1770 pronounced it Eden–like, even though the flowers and greenery were actually growing on some of the ‘worst soils to be found on this planet.’ The area also sported ‘no water, poor anchorages, and shallow shores.’ When Australia’s Botany Bay was considered for settlement in the 1790’s, the transport of a growing number of prisoners was arguably its primary purpose. The result was a penal colony living (alongside a few colonists) a resource–poor subsistence in an area that only looked like Eden. The comparison or irony would not have been lost on these St. Thomas settlers of Irish ancestry.

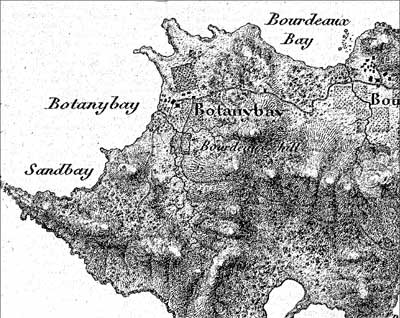

Detail of Estate Botany Bay at the time of the

Hornbeck Map, 1834–1839. Numerous doctor

bills from the Crown Physician Dr. Hans

Hornbeck for his attendance to slaves were

among the unpaid accounts to be reconciled

at Lahougue’s death in 1839. His survey

should be considered fairly accurate, due to

his many visits to the Estate.

As you consult the consolidation table, note that for quite a while, from 1783, with ownership by Armstrong, through William Pannet in 1820, all would be related somehow to James Murphy—his relatives by marriage, heirs, or lawyers. Murphy’s death, on November 17, 1808 resulted in the final expansion of Botany Bay by merger with a portion of his adjacent Catharina’s Hope Estate. His St. Thomas holdings of Botany Bay, Fortuna, Catharina’s Hope, and Dorothea and his St. John holdings of Annaberg, Leinster Bay and Mary’s Point were eventually distributed among his heirs.

An appraisal was done upon the death of Robert Flemming in 1834. This document lists the property’s crop lands, slaves, and livestock, and also provides the first description of the buildings that stood on the estate after the construction of the property’s new sugar factory between 1801 and 1805. There were over 400 acres of unused land, with a value of 0 (!), and 40 acres of cane and 2 acres of pasture valued at 4,030 Rds. The boiling house, still–house and rum cellar were highly valued at 8000 Rds. The enslaved laborers were listed by name; 31 women and 27 men are described by occupation and/or state of health which seemed, disproportionately ‘old, sickly, or dying.’

The enslaved population and area under cultivation continued to decline. (See the Insert–Detail of Estate Botany Bay at the time of the Hornbeck Map, 1834–1839) Under Rasmus William Rasmussen and his heirs, sugar production ended and cattle were grazed 1853–1864. As on St. John, it’s highly likely more sheep than cattle actually grazed at Botany Bay.

SJHS members picnicked among old coconut palms immediately behind the Bay. This narrow coastal plain held a significant prehistoric site occupied once between 700 and 900 A.D. and again between 1300 and 1500 AD. Recovered hand–carved coral slabs may have been associated with a Classic Taino ballgame; a row of stones that ‘appear’ to outline a ball court have been found on–site. The petroglyphs on the northern rocky point of Botany Bay do appear authentic, David notes. In Colonial times the site was the laborers’ village. Given the mixing of successive cultures on the same site, continual recycling, likely ‘above mean high tide’ wave action, and the bulldozed removal of the top layers of this site in the early 21st century, it is unlikely we will ever reconstruct its history.”

Ultimately the site became essentially and officially abandoned, as confirmed by the lack of an entry for Botany Bay in the 1870 census, and by Enumerators visiting the site in 1901 and 1911. In 1915, the last year in which the Danish government compiled an accounting, owner Carl Gustav Thiele reported only 8 acres of the estate cleared for use. In January 1918, when the first U.S. Census was carried out in the Virgin Islands, only 27 year old Conrad Dyas (& family) was enumerated, reporting his situation as ‘renter’ of a ‘general farm.’ The U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey Office in the same year found Estate Botany Bay to be ‘one of the two largest banana plantations on the island of St Thomas.”

From 1916 until 1955, six additional ‘entities’ or persons held title to Estate Botany Bay, when it was bought by Warren H. Corning as a family retreat. Their beach house, pool, and guesthouse still stand alongside the deteriorating sugarworks. Many thanks to the Resort for allowing us entry into a little–seen and beautiful ‘away’ location.