Waterlemon Bay at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century

Members, their guests and visitors, joined historian David W. Knight

for an imagined journey back in time along he shore of Waterlemon Bay.

Organized agro-industrial development in this section of St. John’s Maho Bay Quarter appears to have initially been slow to occur. The first colonial land grant within what would become Estate Leinster Bay was issued to a French-Huguenot refugee, Jan Loisan, in 1721 – some four years after formal Danish occupation of the island. In 1722, another French Huguenot, Isaac Constantin, took up a parcel of land adjoining the Loisan property on its western boundary. This property would later become known as Estate Annaberg. In fact, so many Huguenots settled in the northeastern section of St. John at this time that tax records from the period refer to the area as the “French Quarter.” It could well be that this high concentration of Danish-sanctioned settlers of French background came about due the unwillingness of Danish and Dutch settlers – who made up the majority of early St. John land grantees – to establish themselves within such close proximity to the British on Tortola, who had long threatened to forcibly dislodge the Danes from St. John – as they had the Dutch from Tortola only a few decades earlier.In or about 1755, a Dane by the name of Jens Rasmussen acquired the former Loisan plantation at Waterlemon Bay and merged it with a parcel that abutted its eastern boundary. This property, known as Water Bay, had been granted to Cornelius Stallard in 1725, but had lain vacant and uncultivated since the St. John slave revolt in 1733.

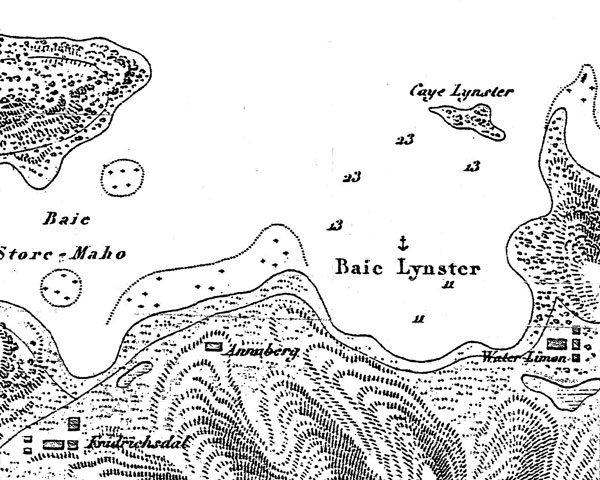

Leinster Bay from a French map of St. John, c1800.

(St. Croix Landmarks Society Library, Estate Whim, St. Croix)

Although Jens Rasmussen was an “absentee” owner, it was under his proprietorship that the first push to transform Waterlemon Bay into a large and viable sugar plantation seems to have occurred. By 1769, when Rasmussen’s sizable mortgage debt on Waterlemon Bay was taken over by Thomas Smith of St. Croix, there was reported to be 100 acres of land under cultivation or in pasture, 50 of which were planted in sugar cane. An appraisal of the estate at this time records the presence of a complete sugar works, with one fireproof wall, a tile roof, and 3 built-in kettles, a mill, a 120-gallon rum still, a warehouse on “piles with a sugar-leaf [thatched] roof, 12 slave cabins, 38 slaves, 2 mules, 9 pigs, and “a dwelling-house, 40 feet by 20 feet, framed in native woods with a sugar-leaf roof.” While the buildings on the Waterlemon Bay plantation are clearly on the “rustic” side for this period, with their frames of “native” wood and thatched roofs made from sugar cane leaves, it was the converted land and 38 slaves that represented the bulk of the property’s value, which was set by the appraisers at an impressive 37,490 silver pieces-of-eight.Over the years, Thomas Smith and his wife, Rebecca Rogers, expended considerable capital to further develop their Waterlemon Bay plantation. In an effort to increase their planting ground, in 1774 the Smiths acquired one-half of a small cotton plantation that abutted their far eastern boundary. This property, which lay in a landlocked valley east of Water Bay (bounding estates Emmaus and Carolina to the south, and Brown’s Bay to the north and east), had originally been granted to William Eason in 1725. The Eason plantation, however, was never profitable and often changed hands. Eventually, after the death of owner James Horne, his heirs liquidated the property, with half of the land being sold to the owners of Brown’s Bay plantation and the other half being sold to the Smiths, who merged it into the broader Waterlemon Bay estate.Thomas Smith died in 1782 leaving the Waterlemon Bay plantation to his three children by Rebecca Rogers, a son, August, and two daughters, Rebecca and Mary – Smith’s six other children by his deceased first wife, Bethiah Ruan, having already received a full distribution of their parent’s estate on St. Croix. As stipulated in Thomas Smith’s will, after his death Estate Waterlemon Bay was to continue to be worked and managed for the sole benefit of his children’s education by their appointed guardian, Dr. Thomas W. Granger. And indeed, tax records indicate that the Smith heirs remained in possession of the property for the next fourteen years, after which time it was sold to a wealthy St. Thomas-based merchant and slave trader, James E. Murphy.Immediately after buying Waterlemon Bay in 1796, James Murphy renamed the estate “Leinster Bay” — presumably in honor of the Irish Provence of his ancestry. Within the year Murphy also went on to acquire the neighboring Annaberg and Mary’s Point estates, along with a portion of the former deWintsberg property known as Betty’s Hope that joined the two parcels.

View looking West from James Murphy’s great house

on a prominent hilltop overlooking Waterlemon Bay.

Following these acquisitions, construction began on a massive state-of-the-art sugar factory on the Annaberg property, while a stately and well-fortified great house began to take shape on a prominent hilltop overlooking Waterlemon Bay. Along the half-mile shoreline that connected these two ambitious projects, Murphy developed a veritable “port city,” flanked on either side by sprawling laborers’ villages, with a total of 126 houses occupied by over 400 enslaved workers. Along the beach at the head of the bay, warehouses, support buildings, and secondary industries soon lined the waterfront: coopers’ shop, blacksmiths’ shop, wood shop, lime kiln, boathouse, turtle corral and hospital. In Waterlemon Bay’s secure harbor, Murphy’s swift, tall-rigged “Westindiamen” were frequent visitors, while the estate’s five boats plied the local waters, engaged as lighters, fishing, or carrying small freight and passengers. Immediately behind the beach, the former Waterlemon Bay sugar factory was refitted and upgraded, doubling its rum production capabilities, while in the deep inland valley and along its flanks grazed 6 cows, 1 bull, 2 calves, 6 horses, 35 mules, and 32 sheep. The graceful hillsides of St. John, in every direction, and as far as the eye could see, were cut and planted in sugarcane.In 1803, James Murphy once again set out to expand his landholdings with the acquisition of the Munsburry plantation, which lay along Annaberg’s southern boundary. Then, in 1807, he purchased the Brown’s Bay estate on the far eastern boundary of Leinster Bay — thereby amassing a total of 1,245 contiguous acres, of which 494 were planted in sugar cane. It was the largest amount of sugar land ever controlled by a single individual in the history of St. John.On November 17, 1808, at the age of 51 years, James E. Murphy died at his Leinster Bay estate house and was buried on a prominent hilltop overlooking his vast domain. At the time of his death Murphy had not only become the single largest sugar producer in the history of St. John, but he also controlled the island’s largest labor force, 591 enslaved workers, of whom more than 60 were skilled crafts-persons.After James Murphy’s death his properties were appraised separately and either sold off to service the accounts of his creditors, or apportioned amongst his heirs. The Leinster Bay plantation was given over to Murphy’s son, Edward C. Murphy, while Annaberg, along with Mary’s Point and Betty’s Hope, became the property of his daughter, Mary Murphy Sheen. After Mary M. Sheen and her husband Thomas died without issue, in 1827 title to Annaberg reverted to the widow of Edward C. Murphy, Catharina Sheen Murphy,* who had married for a second time to Hans H. Berg.**Long a respected civil servant, Hans H. Berg became Governor and Commandant of St. Thomas and St. John in 1853. He retained proprietorship of both Annaberg and Leinster Bay as guardian for his wife and stepson (James Murphy’s grandson, Edward Falkner Murphy, son of Edward C. Murphy and Catharina Sheen) until his death in 1862. By that date, the production and profitability of the former James Murphy properties had been in steady decline for over half a century.

FOR TRUE!

*Edward C. Murphy married Catharina Sheen, who was the sister of Thomas Sheen, who married Edward C. Murphy’s sister, Mary Murphy.** Catherina Sheen Murphy married for a second time to Hans H. Berg, who served as Governor & Commandant of St. Thomas and St. John from 1853 until his death in 1862. Hans H. Berg established his grand estate house overlooking the town of Charlotte Amalie as the governor’s residence on St. Thomas and christened it “Catharinaberg,” in honor of his wife, Catharina Sheen (Murphy) Berg. “Catharinaberg” continues to be the official residence of the Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands to the present day.